This page is a crash course in types of sake. It can teach you everything you need to know to buy sake at shops, read and select from a sake menu, and sell with confidence.

I designed this page to help you get the most out of your Sake Grades and Styles poster. But it has standalone value. So if you know someone that wants to level up at sake fast, feel free to share this page with them.

And if you don’t have a copy, here’s a link to buy the sake poster.

Using This Page

This page expands upon the poster’s information.

You’ll find pronunciations for each grade and type of sake. There’s also more info about them.

Finally, I include links to brands that are textbook examples. Some of these links are to affiliate advertisers and pay me commissions on purchases.

Sake 101: The Grades

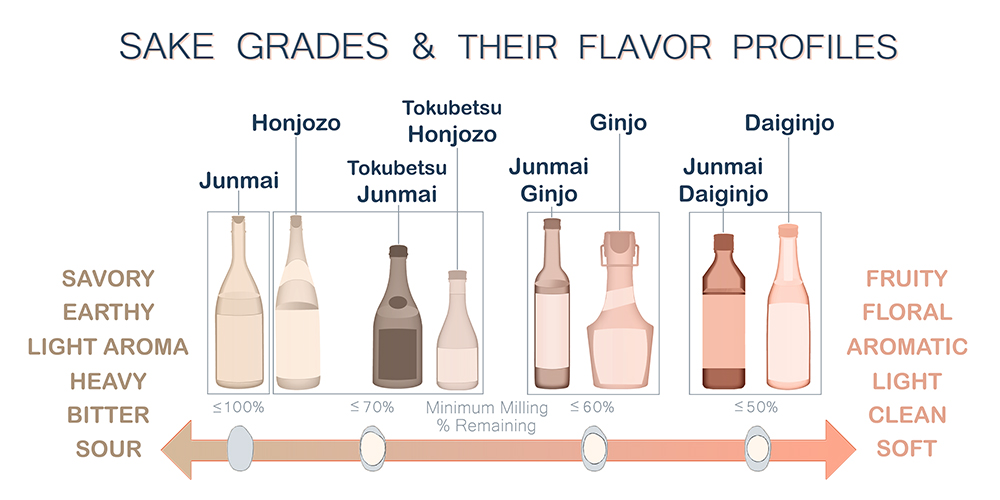

If there is one thing to take away from this poster, it’s that sake grades are important! Every sake has one, and it will be on the label.

The grade is an indication of a sake’s aroma and flavor profile. If you’re new to sake or are struggling to find what you like, learning grades is where to start.

Below are the six official grades of premium sake. I explain how they taste and provide some recommended brands. Please keep in mind that the following tasting profiles of each grade are generalizations.

Junmai

Junmai means “pure rice.” This means that this grade is made only with rice, water, yeast, and koji.

Junmai-grade sake is nearly always savory/earthy with only a light aroma. Delicate junmai do exist, but most of the time, they are rich in flavor. A sour finish (acidity) is also common.

Honjozo

Honjozo-grade is very similar to Junmai. It also tends to be savory and rich. The main difference is that a small amount of alcohol is added to this grade. This tends to make honjozo more aromatic (than junmai) and slightly less acidic.

Adding alcohol to sake would make it stronger. But honjozo and the other alcohol-added sake have water added too. So the final alcohol content is comparable to junmai sake. Interestingly, the added water and the alcohol actually make honjozo taste lighter than junmai.

Tokubetsu Junmai and Tokubetsu Honjozo

Tokubetsu is an unofficial grade of sake. But both tokubetsu junmai and tokubetsu honjozo are fairly common.

Tokubetsu means “special.” There are no specific guidelines for what this means, But in general, tokubetsu junmai falls in between junmai and junmai ginjo. This means it’s a little lighter, fruitier, and smoother than regular junmai. And it’s a bit heavier, less aromatic, and more savory than a junmai ginjo.

And the same concept applies to tokubetsu honjozo. It’s essentially a lighter honjozo with a fruitier character. But it’s not as aromatic, light, and fruity as a ginjo.

“Endless Summer”

Tokubetsu Honjozo

Junmai Ginjo

Junmai Ginjo is a higher grade than junmai and honjozo. The grades with “ginjo” in the name are all harder to make. They require rice that is milled more, careful fermentation, and cold brewing temperatures.

Junmai ginjo is made with only rice, water, yeast, and koji. It’s more aromatic and lighter in body than regular junmai. There are still some savory flavors. But junmai ginjo is fruitier and more floral. The finish is also usually less acidic and smoother.

Ginjo

Like junmai and honjozo, junmai ginjo and ginjo are parallel grades. Ginjo is very similar to junmai ginjo in taste. But because a small amount of alcohol is added, it’s usually more aromatic and lighter in body.

Most ginjo sake is aromatic, light-bodied, fruity, floral, and soft-textured. There are often some savory aromas or flavors in the background.

Junmai Daiginjo

Junmai daiginjo is the highest-grade junmai sake.

How does it compare to junmai ginjo? It’s usually even more aromatic, light-bodied, fruity, and floral. If any savory flavors are aromas are present, they will be faint.

Daiginjo

Daiginjo is the highest-grade alcohol-added sake. It tastes and smells similar to junmai daiginjo: very aromatic, fruity, floral, and light. But the added alcohol makes daiginjo even lighter and more aromatic than junmai daiginjo.

This means daiginjo, on paper, is the most aromatic, light-bodied, fruity, and floral grade of sake.

So at this point, you’ve learned about sake grades. Every sake is assigned a grade. And it will be listed on the label.

Below are the most important styles, or types, of sake. These are in addition to a grade. And a particular brand can have multiple styles. For example, Narutotai “Drunken Snapper”: it’s a ginjo. It’s also a namazake, muroka, genshu, and shiboritate.

Mashing: Shubo 酒母, Moto 酛

Shubo is the sake yeast (fermentation) starter. Koji rice, steamed rice, water, and yeast are the main ingredients. And lactic acid must also be present to prevent spoilage.

The lactic acid is either added (see sokujo below) or created through some other method.

The yeast starter method has a large impact on a sake’s aroma and flavor.

Bodaimoto 菩提酛, Mizumoto 水酛

Bodaimoto is an old-school shubo method of Buddhist origin. It’s considered the first modern sake starter. But it was developed many centuries ago.

Bodaimoto fell out of favor after kimoto was developed. But it’s made a comeback in the last couple of decades.

This style creates lactic acid naturally by first soaking rice in a tub of water. Lactic acid bacteria multiply over a few days. And this water and rice are used in the yeast starter.

This style can be hard to find. And though a couple of bodaimoto brands are relatively mellow most are intense. The flavor is often lactic, sour, and funky.

Kimoto 生酛

Kimoto is a traditional shubo method that replaced bodaimoto. Similarly, it’s a natural way of propagating lactic acid.

For kimoto, the laborious yamaoroshi (山卸し) process is used, where paddles mix the yeast starter into a puree. This produces lactic acid, which protects against spoilage. Cold temperatures are required, plus lots of stirring and time.

This type of sake is hard to make, so it accounts for only around 1% of total production. But if a brewery went through all the trouble of making kimoto, they will almost always say so on the label.

What’s it taste like? Kimoto sake is generally earthy and acidic. It’s usually very complex. And this style is also often good served chilled or warm.

Yamahai 山廃

The yamahai method is much newer than kimoto. And it tastes very similar but is easier to make. So it’s much more common.

Brewing yamahai requires a warmer mash temperature. The lactic acid slowly develops on its own, replacing the hard work of the yamaoroshi process.

Like kimoto, yamahai is usually pretty good warm or chilled.

Sokujomoto 速醸酛

Sokujomoto is the most common mash starter by far. And the term rarely appears on the label.

Sokujo was developed around the same time as yamahai. This method uses commercial lactic acid which is added directly to the mash. It inhibits unwanted bacteria and allows for quick and easy fermentation.

This efficient method makes clean, elegant, and smooth sake.

There’s also a substyle of sokujomoto worth knowing about. Kountouka (高温糖化) is a variation where a very high temperature is used. This speeds up the yeast propagation process even more. And it tends to make very fruity and smooth sake.

Pressing: Jozo 上槽, Shibori 搾り

You cannot make sake with this crucial step, which separates the solids (lees) from the liquid. Before, it’s more like an alcoholic rice porridge.

Brewers typically press with an automatic press, the traditional fune, or using the hanging bag method.

Shizuku 雫

Bags suspend the mash, and only what drips freely is collected. This hanging bag method is called fukurozuri. And sake it makes is called shizuku.

Shizuku is a difficult and inefficient older method. And it’s rare and expensive. But shizuku sake is delicious. It’s nearly always a junmai daiginjo or daiginjo. And it’s smooth, elegant sake, and complex.

Arabashiri あらばしり and Nakadori 中取り

A fune is an old-school rectangular press. Cloth bags are filled with freshly-fermented sake and stacked inside. A pressure plate is lowered onto the bags, separating the rice solids from the sake.

Arabashiri is a vibrant and bold sake that pours freely inside a fune without pressure. Once all the free-run sake is collected, light pressure is applied to extract more. This sake is called nakadori. It’s considered the best portion.

Most sake is made by mixing the arabashiri and nakadori. Arabashiri is often bottled on its own. Nakadori is much harder to find.

Tobinkakoi 斗瓶囲い

Tobinkakakoi is sake collected in a tobin, which is an 18-liter bottle. And it allows for brewers to divide and select only the best-tasting sake from a press. Usually, either a fune or the hanging bag method are used.

Tobinkakoi didn’t make it onto the Sake Grades and Styles Poster because it’s so rare. Even though many breweries make it, it’s mostly limited to sake brewing competitions. It’s sometimes sold in limited quantities at extremely high prices.

Shiboritate しぼりたて

Shiboritate is bright and youthful “fresh-pressed” sake. It’s bottled shortly after pressing, usually unpasteurized. Any pressing method can be used to make shiboritate.

Shiboritate is released early in the brewing season, becoming available in late fall or winter.

Pasteurization: Hi-ire 火入れ

Sake spoils easily. So it’s typically pasteurized after pressing and again at bottling.

Briefly heating the sake stops all microbial activity. This ensures it will remain stable.

However, pasteurization also mellows the flavor and reduces intensity.

Namazake 生酒

Namazake, or simply nama, is completely unpasteurized sake. It’s bold, sour, and sometimes bitter. Namazake tastes nothing like conventional, twice-pasteurized sake. The acidity can be on par with tart white wine.

Most breweries produce a nama each spring as one of their first releases of the season. It’s typically only available in limited quantities. And enthusiasts will buy it up quickly before the season’s supply sells out.

Namazume 生詰め

Namazume is pasteurized once. This happens shortly after the pressing stage.

Sake is often passed through an immersion coil in a hot water bath. The result is a sake that’s more acidic and vibrant than regular sake. But it’s not nearly as sour and bitter as namazake.

Namachozo 生貯藏

Namachozo has also been pasteurized once. This time, right before or during bottling.

Like namazume, namachozo’s character sits between namazake and conventional twice-pasteurized sake.

Hiyaoroshi 冷や下ろし, ひやおろし

Hiyaoroshi is a fall-release sake that’s typically bright and flavorful.

It’s a seasonal style that’s brewed in spring, cold-stored over the summer, then released in the fall. Hiyaoroshi is often only available in the fall in limited quantities.

Most hiyaoroshi are pasteurized once after pressing (namazume). However, hiyaoroshi is often a little more mellow and savory than regular namazume.

Other Styles

Below are a mix of common brewing choices and specialty styles.

Muroka 無濾過

After pressing, most sake is filtered again to remove fine sediments. Charcoal filtration is often used to make the clearest and cleanest-tasting sake possible.

But muroka is made without charcoal filtration. And rarely, some muroka is completely unfiltered.

This style is full-bodied and rich. And it usually has a straw to yellowish color.

Muroka, nama, and genshu brewing techniques are often combined to make a super-powerful and intense sake.

Genshu 原酒

Most sake is cut with a small amount of water. This reduces the alcohol content and makes sake smoother and lighter-tasting.

Genshu sake is undiluted and often strong, mildly sweet, and full-bodied. The alcohol content of genshu ranges from 16-22% ABV and averages 18-20%.

When genshu appears on the label, it’s a warning that the sake will be strong!

Nigori にごり

AKA: Nigori-shu にごり酒

Nigori is one of the most popular styles of sake. The word means “cloudy.” And it’s often sweeter, thicker, and grainier than clear sake. The more clouds (lees), the more pronounced these traits can be.

Nigori is made by coarse-filtering the mash or by adding the lees back into clear, pressed sake.

Usu nigori うすにごりis a thinner, less cloudy variation of nigori.

Serve nigori from cold to room temperature. As a general rule, this is not a good style to heat up.

Sparkling スパークリング

AKA: Happo-seishu 発泡清酒

Sparkling sake is a variable, newer style. It’s been growing in popularity over the last couple of decades.

There are many ways to make bubbles. Forced carbonation is the most common for affordable brands. Secondary fermentation in bottles or tanks produces finer and longer-lasting bubbles. And traditional-method wine techniques, similar to Champagne production, are all used to create CO2.

Most sparkling sakes are light, low alcohol, and sweet. Some are cloudy. Dry sparkling sake is higher in alcohol and aims to compete with sparkling wine.

Sparkling sake makes a great aperitif. And it’s also very good with fried food like tempura. Just be sure to serve it chilled.

Tanrei 淡麗

Tanrei is a marketing term for light and elegant flavored sake. There is no specific brewing choice that yields tanrei sake.

Tanrei is often brewed dry tasting (see karakuchi below), as well. And the sake from Niigata helped make this style famous.

“Tanrei”

Junmai

Karakuchi 辛口, O-karakuchi 大辛口

Karakuchi is exceptionally dry sake. The term “extra dry” means roughly the same thing.

Super dry sake is all the rage right now. It’s usually best when served chilled. But some examples can be delicious when served hot.

Taru Sake 樽酒

Taruzake is cedar barrel-aged sake. All sake was brewed and stored in cedar before steel tanks became widespread. But nowadays, only a few brewers are making it.

This type of sake has a flavor of spicy, herbal cedar. Some brands and mellow and elegant, while others are intense and piney in flavor.

Chilled taruzake is the sake equivalent to barrel-aged chardonnay. But it’s also usually very good warm.

Koshu 古酒

Koshu means “old sake.” Most koshu has been aged for three or more years. Some famous examples are aged 20 years or more.

The longer the time spent aging, the nuttier, more oxidized, and savory koshu tastes. Color becomes darker too. When most people think of koshu, it’s this dark savory style that comes to mind.

But some koshu are aged at frigid temperatures so the aging process isn’t as extreme. This is often done for high-end grades like daiginjo. And this type of koshu looks normal and tastes settled and complex.

Kijoshu 貴醸酒

Kijoshu is a rare style of sake. To make it, the fermentation step is modified. Instead of adding brewing water, finished sake is used. The alcohol stops yeast from creating more alcohol. But it doesn’t stop the koji from making more glucose (sugar) from the rice.

The result is a very sweet and creamy style of sake. With age, it can have deep umami, color, and Sherry-like qualities.

Kijoshu is amazing with ice cream or strong cheese.

Conclusion

Learning types of sake can seem daunting. But if you take a little time to apply this info to what you’re drinking, you’ll be a pro in no time.

If you want to speed up your progress, I suggest taking some notes. Write down the names of sake you taste, the grade, and any substyles like kimoto, nigori, etc. The brand name and the grade are easy to find on the label. You may have to do a quick Google search to learn about a sake’s various styles.

If you want a guide to help you on the road, download my free Essential Sake ebook. It’s a shorter version of this content and perfect for use at shops and restaurants.