A pot still is the classic spirit still used for many spirits like malt whisky, brandy, rum, and shochu. Artisan and/or heavier-flavored spirits often come from a pot still. And lighter and/or more industrial spirits like grain whisky, vodka, and industrial rum typically use the more modern continuous column design.

Pot still distillation is a batch process. The initial distillation turns fermented wash into a low-alcohol spirit – usually around 25% for whisky. The still is cleaned, and the once-distilled spirit returns to the still. After a second distillation, the spirit is often around 55-70% abv. Many single malt Scotch and Japanese whiskies are only distilled twice. Irish whiskey and brandy are often distilled three or more times.

Three or more distillations result in an even cleaner, higher-proof spirit. However, because pot still distillation is batched, it’s labor-intensive. So continuous column stills are much better for several distillations.

Copper vs Steel

Copper is the most common material for pot stills for Western spirits. The reason is copper is a catalyst that strips out heavy elements (congeners) from spirits.

Stainless steel pot stills are typical for shochu distillation. Shochu is essentially distilled sake, which is pure and low in congeners. So copper isn’t required for smoothing out the flavor. Additionally, stainless steel is stronger than copper and ideal for using vacuum distillation techniques.

Pot Still Design

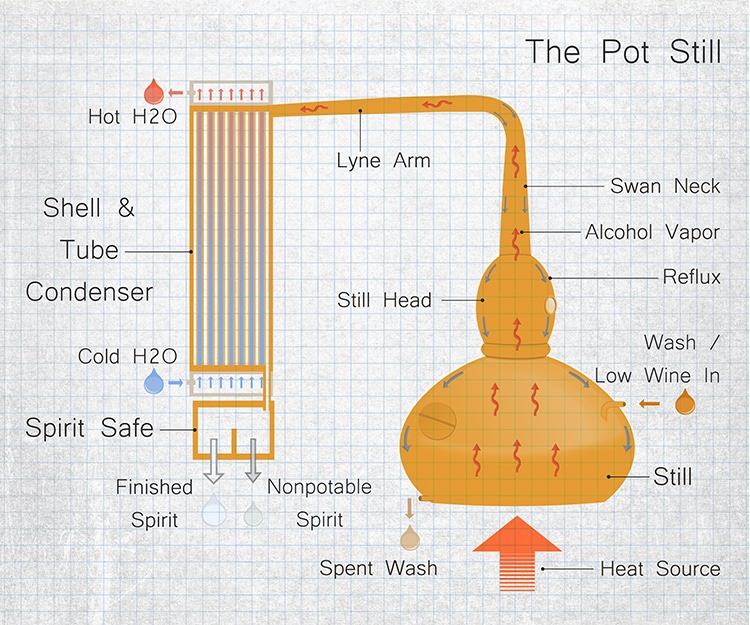

Pot stills have a simple design, consisting of a still and a condenser. The bottom is round, leading to a long tapered swan’s neck or Lyne arm. This tapered connection links to the condenser, which consists of a spiral tube surrounded by a cooling cold water jacket.

The pot is where beer, wine, or sake is heated. Alcoholic vapors rise into the swan’s neck or Lyne arm and are cooled into liquid in the condenser.

How Still Shape and Size Affect Flavor

The shape and size of copper pot stills has a profound effect on the flavor of the spirit. The more contact with copper, the lighter and smoother the liquor.

Bigger and taller stills allow for more contact between alcoholic vapor and copper, producing a lighter spirit. Shorter, smaller copper pot stills yield richer, heavier spirits.

Other Factors Determining Pot Still Spirit Quality

Reflux and distillation speed are two additional variables. Reflux is vapor that condenses in the still and falls back into the wash instead of passing into the condenser. More reflex equals more copper contact and a lighter spirit.

The shape and angle of the Lyne arm influences the amount of reflux, as does the still’s height and shape.

Speed of the distillation is also impactful. The temperature of the still and wash influences this variable. A fast distillation run means less copper contact and a heavier, rougher spirit. The opposite can be said of a slow distillation.

The Condenser

The condenser has a big impact on the whisky character. The most common type for a pot still is the shell and tube. Cold water flowing through pipes cools and condenses the alcoholic vapor from the still. Droplets of alcoholic liquid form which increases contact with the copper shell (housing).

The worm and tub condenser is the other major type. It’s an older design than the shell and tub and few commercial distillers use them due to higher maintenance issues. The resulting whisky is typically full-flavored and funky.

The Pros and Cons of Using a Pot Still

Pot still distillation is a laborious process. It takes more time, money, energy, and is less efficient than most other designs. The quality of the whisky it can produce is high, however. More concentration of flavors and more flavor from the base ingredients will be displayed.