Last Updated: 4/2/2021

Omachi is one of the most important players in the sake world. This heirloom rice strain is used for some of the greatest sakes in existence and is beloved by sake connoisseurs across the globe.

This page takes a look at this iconic sake rice in detail. Learn its history, where it’s grown, how its sake’s taste, popular brands brewing with it, and more.

The Origin Story of Omachi Rice

Omachi is an heirloom strain of rice with a long and distinguished history. Jinzoo Kishimoto is said to have discovered the rice strain in 1859. While travelling he noticed some rice that was extremely tall with heavy grains. As a rice farmer, he recognized it for its unique quality and took two whole plants home.

These two plants were used to propagate the rice strain. It was originally given the name Nihongusa, two plants, for this reason. The name would later change to Omachi, since that was where Kishimoto-san was from.

The height of Omachi poses a problem, however: it’s easily knocked over by strong winds. For this reason, it’s use died out for some time.

In 2021, the Okayama Agriculture Experimentation Center produced a pure line selection of Omachi, reviving the grain.

Where is Omachi Grown?

Okayama is both the ancestral home for Omachi, and today it’s still where the vast majority of it is grown. Over 2,700 metric tons were harvested in 2019. This ranked fourth overall in total shuzokotekimai (sake rice) production.

Hiroshima is the next most important location for Omachi production. In 2019, The prefecture produced 126 metric tons. Most of this was of very high quality.

Fukuoka produces a very small amount of the grain, but it’s of decent quality.

Lastly, Osaka, Kagawa, Oita, and Chiba produce trace amounts of this heirloom rice. The quality from these prefectures isn’t great, however.

Unique, Localized Strains

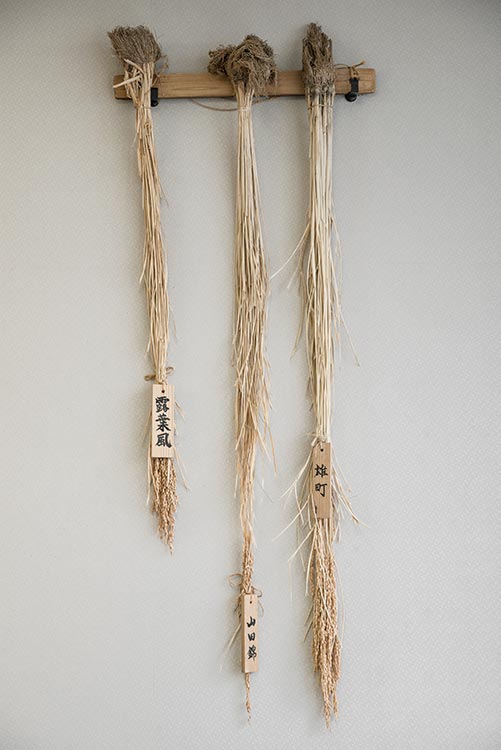

A variety of localized sub-types of Omachi have developed from the original pure line was selected in Okayama.

The rice grown in Takashima, Okayama is considered the best. Not far behind is Bizen Omachi (備前雄町), which is also grown in Okayama. Akaiwa Omachi (赤磐雄町) is another superior, local adaptation of the original pure line selection.

Hiba (比婆雄町) and Funaki Omachi (船木雄町) from Hiroshima are also important localized sub-strains.

Finally, Kinai Omachi (畿内雄町) from Kawachi, Osaka is also known for its high quality.

Growing Omachi

Omachi is a very tall sake rice type. The stalk height can reach 120 cm, or nearly 4 feet. Combined with large rice grains, Omachi is very easily felled by strong winds (lodging). Rice plants that are knocked over are lost. This makes site selection very important. Protection from wind is critical.

Wind isn’t the only threat to the rice plants. Many insects love to eat the leaves and stalks, and so do deer.

Despite these challenges, Omachi is still produced in large volumes each year.

As mentioned before, Omachi is a pure strain of sake rice. It has a few unique and localized sub-strains, but it is not prone to mutation.

Characteristics of the Rice Grains

The grains of Omachi are large. The average weight for 1000 grains, a common metric, is an above-average 27.3 grams.

Omachi also has a very high rate of shinpaku (≈ 90-95%) and relatively high protein content (5.8%).

The large grains and ample shinpaku are great for koji production and sake brewing.

However, the grains crack easily during milling. Since cracked grains are not ideal for making quality sake, this limits how much milling can be achieved. The typical maximum seimaibuai for Omachi is around 45% (55% removed).

Brewing with Omachi

As mentioned previously, Omachi has large grains but is prone to cracking during polishing. This means it is rarely used to brew highly polished ultra-daiginjo (milled below 40% remaining). Otherwise, it’s a popular rice to use for sake brewing.

Characteristics of Sake Made with Omachi Rice

Sake made with Omachi rice tends* to be mildly aromatic, earthy, rich, and complex. An herbal quality is typically present. Ricey flavors are also common. A dense texture is also common.

* It’s important to state that sake rice is not the equivalent to grapes in wine. Grapes, and where they’re grown, make the wine. Its aromas and flavors are determined in the vineyard and with the choice of grape grown there.

Sake rice strains do have their own flavors they add to a sake. However, sake brewing is very complex. How rice mills, how koji reacts to it, what yeast is used, the water choice, and the steps the toji (brewer) choose to take to brew the sake are all important variables. The rice type alone does not dictate the flavor of any particular sake.

Shop Popular Sake Brewed with Omachi Rice

We may earn commissions on qualifying purchases.

Sakura Muromachi Junmai Ginjo “Bizen Maboroshi”

Seikyo Omachi Junmai Ginjo

Tamanohikari Junmai Daiginjo

Famous Sake Rice Types with Omachi Roots

Despite Omachi’s restraint in mutating, through selection and crossing, its qualities have been passed on to many popular sakamai.

The recently revived Watari Bune rice strain is thought to be merely an Omachi selection that had been successfully cultivated in Kanto. Watari Bune was also at one time the most widely grown rice in the United States and was crossed to make the now ubiquitous Calrose varietal.

Yamada Nishiki, Gohyakumangoku, Tamazakae, Ginfubuki, and Koshitanrei are just a few of the major sake rice types that can all trace their lineage back to Omachi.

Follow the Japanese Bar on Social Media

Connect with our latest posts, the newest Japanese beverage info, and get exclusive promotional offers. Level-up your sake IQ!