Japanese whisky captivates the world with its unparalleled craftsmanship and exquisite flavors. But whisky from Japan is also elusive, expensive, and sometimes downright fraudulent.

My guide is designed to help you become a more informed buyer. Discover the good, bad, and ugly of Japanese whisky. The table of contents below will help you find what you’re looking for.

From left to right: fake whisky, rice whisky (aka shochu), and iconic Japanese whisky.

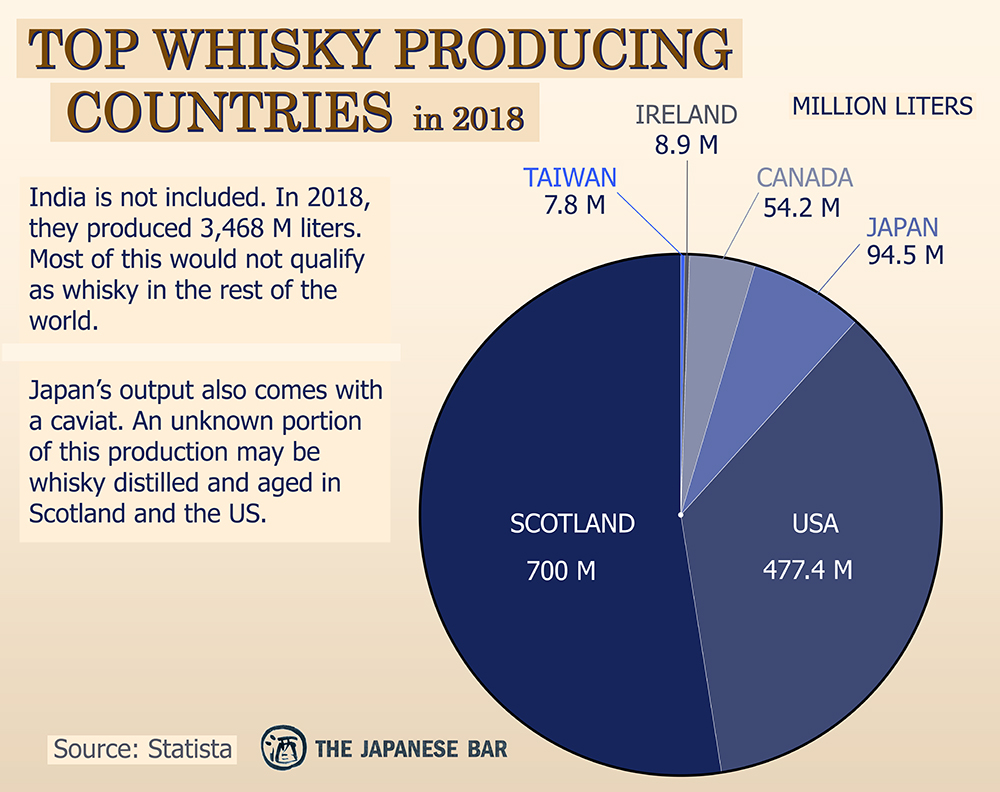

Japanese Whisky in 2023

The Good:

- New, legit distilleries big and small

- Increased production from Nikka and Suntory

- Move towards regulation, transparency

The Bad:

- High prices likely to continue

- Fakes not going away anytime soon

After nearly a century of relative obscurity, Japanese whisky ascended to the top of the market. Delicious brands like Yamazaki, Hibiki, and Yoichi lead the way. And stocks from phantom distilleries like Karuizawa and Hanyu are among the world’s most expensive bottles.

But the journey to 2023 was rocky, with negative effects still being felt today. Extreme high prices, low value, and numerous fakes are the norm, making Japanese whisky the ultimate buyer-beware whisky category.

For the last decade, numerous new brands of “Japanese whisky” have popped up. These nefarious products are simply cheap imports from Scotland and Canada with kana on the label. And for nearly as long, shochu has been finding its way into bottles in the form of “rice whisky.” Some of these are actually pretty good. Regardless, transparency isn’t a strength of the category.

Luckily, things are changing. In 2021, the Japan Spirits & Liqueurs Makers Association adopted a set of Japanese whisky standards. These voluntary rules align with other major whiskies like Scotch and Bourbon. The regulations don’t fully kick in until early 2024, but many of the Association’s members have already conformed to the rules.

Now this won’t stop a lot of these new phony brands. So it’s still a good idea to research any brands you’re unfamiliar with before you buy. This guide will help with that (so will my whisky map).

And finally, the extreme prices for Japanese whisky bottles relative to other whiskies aren’t going down anytime soon. But there are still values out there.

Next, I dive into why Japanese whisky is so expensive.

Why is Japanese Whisky So Expensive?

Years of under-production, coupled with increasing demand, resulted in famous products disappearing and prices soaring.

The popularity of Japanese whisky is at an all-time high. At the same time, supplies of the most sought-after brands are incredibly low.

In response, the major producers Suntory and Nikka have discontinued many of their famous age statement brands. Hibiki 12, Yoichi 15, Miyagikyo 15, Taketsuru 17–all gone. Nikka was especially heavy-handed, essentially removing all of their age statement brands.

Meanwhile, many of the aged stocks that would have gone into these popular products have been diverted into new non-age statement (NAS) brands. This practice does produce really good whisky but also introduces much younger whiskies into the blend.

Another side effect of the red-hot market has been staggering increases in price. The vanishing quantities of discontinued bottlings have fueled much of this. This has led collectors and enthusiasts to speculatively acquire other marquis labels. Examples of this include Yamazaki 18 ($850+), Hibiki 21 ($900+), and Hakushu 18 ($500+). Prices for these bottles have nearly doubled in just a few years. There are not many of these whiskies left on retail shelves, and will they be discontinued next?

The above dynamics of supply and demand are easy to understand. Unfortunately, Japanese whisky has a couple of other issues that are adding confusion to the market. Both are centered around labeling laws. One of them is fairly innocuous, but the other is malignant.

We’ll start with the lighter issue which is tied to Japan’s native spirits: shochu and awamori.

Japanese Rice Whisky – AKA: Koji Whisky

Rice whisky is a reasonably new product available in the United States. But all is not what it seems.

How Japanese Rice Whisky Developed

Due to protectionist international trade agreements, shochu cannot have too much color.

This agreement allowed shochu and Japanese whisky into European markets. Dark, aged shochu was deemed a threat to whisky and was banned for protectionist reasons. Since malted barley isn’t used, shochu is not considered whisky either—in Europe anyway.

Despite this, some cask-aged genshu (undiluted) rice shochu was being produced in Kumamoto, Japan. And it was delicious. Unsure of what to do with it, the producers left this shochu resting in casks.

In the United States whisky isn’t required to use malted barley. Eventually, word got out about the Kumamoto distillate, and soon after, it hit the US market.

The two pioneering brands are Ohishi and Fukano. Both of these brands are labeled as rice whisky. They also list malted rice as an ingredient. But make no mistake, this is marketing language. The malted rice is actually koji rice.

Whisky or Shochu?

These new shochu-based whiskies do taste remarkably like whisky. The effects of barrel aging on spirits are profound. So much so that, when giving enough time in-barrel, almost any grain-based spirit will eventually resemble whisky.

Koji whisky is a common name given to this new category. Many other brands have popped up recently. For now, the two originals are still the best.

Koji whisky is here to stay, and that’s fine with us. Aged shochu can be magnificent. And when it’s aged in oak casks, the results looks, smell, and taste like whisky. You also get some characteristics from the base rice spirit: malic fruit and citrus, pretty aromatics, a light body, and a clean finish.

Brands like Kujira and Meiyo have been bottling and selling extensively aged Awamori as rice whisky. We also expect to see koji whisky made from barley and sweet potato shochu on the market eventually.

Japanese Whisky: Authentic vs Fake

Finding authentic Japanese whisky is a challenge. And even defining what authentic means isn’t straightforward.

Labelling Laws

Today, the biggest issue affecting the reputation of Japanese whisky is its lax labeling laws.

Specifically, as long as whisky is bottled in Japan and contains a few drops of authentic Japanese whisky, it can be labeled as “Made in Japan” or “Product of Japan.”

A lot of Scotch and Canadian whisky ends up being bottled as such, along with some whisky from the United States.

The practice of using imported whisky to make Japanese whisky has been a long-standing practice. Even big names like Nikka and Suntory do it. And this isn’t entirely for nefarious reasons. But that didn’t stop many unscrupulous sellers from taking advantage of consumers.

Blended Japanese Whisky’s Dirty Secret

Blended whisky, made entirely in Japan, is a rarity. For the most part, only the biggest producers with multiple distilleries are doing it. Even then, many of their brands rely on imported whisky for their blends.

Reliance on imported whisky has been a practice in Japan since the beginning of the industry. Many domestic-only brands are made with a significant proportion of these imports.

One of the reasons for this is because the whisky industry in Japan does not cooperate. They’re fiercely competitive. Unlike in Scotland, companies don’t trade whisky. This makes it very difficult for producers to make blended whisky.

This applies to many brands on the export market, as well. Even award-winning whiskies like Nikka From the Barrel is using imported whisky in its blend.

In general, Japanese single malts are more likely to be made in Japan. But as we’ll discuss next, that assertation has been increasingly under threat.

Fake Japanese Whisky

The increase in Japanese brands made entirely with imported whisky has been explosive.

Without naming names, 18 and 12-year aged “Japanese” single malts from Scotland have appeared on the market, with sticker prices similar to Yamazaki. Countless unsuspecting customers paid high prices for these nefarious labels. This has tarnished the reputation of Japanese whisky.

Will there ever be some transparency with Japanese whisky?

Maybe.

Steer clear of fakes and koji whiskies with this excellent Nomunication infographic.

Japanese Whisky Industry Transparency and Reform

Reforming this hot mess has begun with a couple of producers that care taking small steps in the right direction.

Japanese World Blends

Instead of labeling blends of imports and domestic whiskies “Japanese Whisky” or “Made in Japan,” a few producers have opted for a more transparent approach.

Whiskies labeled as world blends began hitting shelves, starting with the authentic whisky producer Chichibu. Consumers have the benefit of knowing the truth about these whiskies, and Chichibu can offer a more affordable product without sacrificing their brand’s credibility.

Suntory has followed suit with their Ao World Blend.

That’s not a long list! But let’s hope more distilleries jump on board.

Voluntary Label Reform

The 2021 announcement of voluntary label standards for Japanese whisky has caused a stir.

Enthusiasts have heralded this as the dawn of a new age in transparency. Many regular consumers cried foul, having just realized that they had been duped. The truth is complicated, but the new standards are a net positive.

The Japan Spirits and Liqueurs Makers Association is behind these new voluntary standards. Many of the biggest names in Japanese whisky are members. Some of the biggest offenders are too. Their idea is to bring the definition of Japanese whisky in-line with the rest of the world’s prominent whisky-producing countries.

According to the Association, for a whisky to be called “Japanese whisky” or “made in Japan,” it must meet several requirements.

First, it must be made from cereal grains. Malted grains must always be a component of this. Saccharification, fermentation, and distillation must all occur in Japan. And the ABV of the distilled spirit has a maximum of 95%.

Furthermore, wood casks of less than 700 liters must be used. This aging must occur in Japan and for a minimum of three years.

Finally, the whisky must be bottled in Japan at a minimum of 40% ABV. The use of caramel coloring is allowed.

Check out this list (in Japanese) of the union’s members to get an idea of which brands will begin complying with these new standards.

The Story of Japanese Whisky

Japanese whisky wasn’t always a global superstar, though it started with a bang.

For hundreds of years after its creation, whisky was foreign in Japan. The country’s isolationists policies came to an explosive end in 1853. That year, American Commodore Matthew Perry, with a small fleet of technically advanced warships, steamed into Tokyo Harbor and demanded Japan open up trade. The intimidation tactic worked, and the Convention of Kanagawa was formalized. Trade between Japan and the West was reopened.

As a parting gift, the Americans left a 110-gallon barrel of whisky. It was a smash hit, but the Japanese had no idea how it was made.

The early whiskies made in Japan were horrible. Producers were mixing grain spirits with all kinds of things (perfumes, juices, spice) as an approximate. In 1918, an American Expeditionary Force officer in Hokkaido wrote about this nefarious stuff, a local brand called Queen George.

“All the cheap bars have Scotch whiskey made in Japan … If you come across any, don’t touch it. It’s called Queen George, and it’s more bitched up than its name. It must be 86% corrosive sublimate proof because 3,500 enlisted men were stinko fifteen minutes after they got ashore. I never saw so many get so drunk so fast.”

Major Samuel I. Johnson

Modernization: The Rise of Whisky in Japan

Officials in Japan realized that their isolation had left them vulnerable to other countries. They dispatched scientists and ambassadors around the world to learn about modern science, governance, and education.

One of these men was a chemist named Masataka Taketsuru. He traveled to Scotland to formally learn whisky production, taking several apprenticeships at whisky distilleries in Speyside and Campbeltown. Taketsuru would also meet his future wife Rita Cowan on this trip.

Taketsuru returned to Japan with Rita and a new understanding of the whisky-making process.

At this time, another Nippon whisky pioneer was building a beverage empire. Shinjiro Torii had a vision of creating Western-style liquors to suit the Japanese palate. His original hit was Akadama Port Wine. This sweet fortified wine, which featured a provocative ad campaign, produced the revenue for Torii’s real dream: producing authentic Japanese whisky.

Torii had heard of Taketsuru’s expertise and hired him to lead the establishment of Yamazaki. The iconic distillery was opened in 1923 and was the first operating facility in Japan.

The two titans of Japanese whisky did not get along. Making matters worse, Yamazaki was beset by production issues and its early whiskies weren’t that good. In 1929, the company released Suntory Shirofuda (White Label). It was the first authentic Japanese whisky. And it bombed.

The accumulation of these events was too much for Torii to handle. He demoted Taketsuru, who went on to quit.

Torii and Yamazaki would right the ship. Taketusuru’s journey didn’t end either. Rita connected her husband with several investors that would back the creation of a new whisky distillery. It didn’t happen overnight, but by 1936, the Nikka Yoichi Distillery was founded in Hokkaido.

In 1937, Suntory Kakubin was released, becoming the most successful Japanese whisky of all time.

The Yamazaki and Yoichi distilleries would begin a fierce competition that continues to this day. In their early year, the market for their products was mostly limited to wealthy businessmen and the military. The latter had a particular affinity for their whiskies.

During WWII, the two companies would be commissioned to supply the Japanese military with whisky rations. This kept the two companies afloat during a tumultuous time.

After the war, Japanese whisky steadily gained prominence domestically. Other distilleries began appearing to meet the demand. Craft distillery Hanyu came about in 1946, and legendary Karuizawa ten years later. Suntory and Nikka founded new distilleries as well. The Miyagikyo, Hakushu, and Chita distilleries were all founded between 1969 and 1973.

By the early 1980s, whisky was at peak popularity in Japan. It was around this time that things took a turn for the worse.

Whisky and the Salaryman: The Industry Goes Bust

International trade reform in the mid-’80s forced Japan to open its markets and standardize its alcohol taxation with the rest of the free world. These actions made shochu more affordable, right when its popularity was surging amongst younger drinkers.

This change in consumer taste occurred just as the economy in Japan began to stagnate. A period of time known as the Lost 10 Years would see the salaryman become a symbol of the collapse. Shochu consumption continued to rise, as did beer.

A number of distilleries closed: most notably Hanyu, Karuizawa, and Mars Shinshu. Suntory and Nikka both significantly reduced their output. The lack of supply mentioned previously on this page can be attributed to this period of low production.

Around the year 2000, signs of positive change began to emerge.

Awards and a Historic Comeback

Starting with a Yoichi 10-year single malt in 2001, Japanese whisky began winning a large number of international whisky awards. Since 2007, they’ve been dominant.

A promising new brand would also make an international splash. Ichiro Akuto founded Venture Whisky in 2004. His family had owned Hanyu, and Akuto bought up much of their stocks, along with whiskies from Karuizawa and Kawasaki. These were blended and bottled as the Card Series under the brand name Ichiro’s Malt. The demand was staggering. Akuto used the capital to found the Chichibu Distillery in 2007. The first release from Chichibu sold out in under 24 hours!

Other producers would emerge to meet the surging demand. Mars Shinshu resumed operations in 2011. Eigashima’s White Oak Distillery increased its quality and production after decades of catering to domestic drinkers. And most recently, the Akkeshi Distillery was launched to produce terroir-driven whiskies in remote Hokkaido.

Want to know more about Japanese whisky history?

We have a whole page about it just for whisky nerds! Take a deep dive into the history of Japanese whisky.

Finding, Buying, and Collecting Japanese Whisky

Whatever kind of Japanese whisky you’re looking for, we’ll help you find it.

There are many great Japanese whiskies available at different price-points. It all depends on what you’re after. Yes, the prestige brands and discontinued classics are fetching astronomical prices. But it’s also true that some delicious authentic whiskies have emerged for the budget-minded Japanese whisky enthusiast.

General Tips for Finding Authentic Whisky at a Fair Price

Shopping for Japanese whisky can be a bewildering experience. As mentioned earlier, there is a combination of factors that make this the case: imported fakes, koji whisky, and a shrinking supply of iconic brands.

The best place to start shopping for Japanese whisky is online. There are tons of delivery options available these days, which is a trend that will continue to increase.

Do not rush out and buy the first whisky you find. Chances are, there is a better deal out there. With Japanese whisky, it pays to shop around!

Sites like Wine-Searcher are a useful tool to see what local retailers are charging. Once you’re familiar with the range of prices for your desired whisky, you can make a better decision on what you’re willing to pay.

Entry-level Whiskies from Japan

Cheap authentic Japanese whisky is nearly an oxymoron. Only a select few brands exist. There has been a proliferation of cheap fakes, however, so know your whisky!

Suntory Toki ($30), Mars Iwai 45 ($35), and Mars Tradition ($35) are all brands that are widely available. These are great options for mixing. Their low prices also mean that restaurants and bars have affordable Japanese whiskies to use in their cocktail programs. Finding and purchasing these whiskies is fairly straightforward. There are many delivery options available, depending on your state’s laws. Many large liquor stores will also carry them. Even Costco is a good place to check.

Moving up in price, a lot of options begin to emerge. Akashi Blended ($45) is a good value with wide distribution. Nikka Coffey Grain ($60) and Coffey Malt ($75) have both been temporarily discontinued, but supplies are still ample. These whiskies may go up in price in the short term. Both are outstanding options. Lastly, Kaiyo whisky has emerged over the last few years and appears to be authentic. Where they source their whisky is a closely guarded secret, however.

Marquis brands begin emerging at around $80. Examples include Nikka’s Yoichi, Miyagikyo, and From the Barrel, as well as Hibiki Japanese Harmony. The availability of these whiskies online and at retail shops is great enough that you should shop around. There are some over-priced bottles out there you’ll want to avoid.

This also holds true for purchases at restaurants and bars. A common goal for beverage program liquor cost is about 20%. This would mean a $22 price for a 1.5-ounce pour from a $75 (wholesale) bottle. Every program is different but beware of prices that are much higher than this.

What about other Japanese whiskies? If you haven’t already check out the previous section on koji whisky and fakes. Some of these whiskies (Fukano and Ohishi) are pretty tasty. Just make sure you know what you’re buying first.

Shopping for Mid-Level Japanese Whiskies

Here we discuss whiskies with an average retail price from $100-$250. There are some really great whiskies in this price range. Of course, these prices would represent the high-end of most other whisky categories like Scotch, Irish whiskey, Bourbon, etc.

There are a few marquis brands in this price range. Akashi Single Malt ($100), Yamazaki 12 ($130), and Hakushu 12 ($170) come to mind. The Hakushu has been partially discontinued and has seen prices rise quickly. It’s debatable if this is really a collector whisky, as it hasn’t entirely disappeared from the market.

The list of imposters is very long at this price range. Again, know what you’re looking for ahead of time. Never heard of the brand? Do some research. Is the Scotch used to make Kurayoshi 18 tastier than Highland Park 18? No, it’s not. So why pay more for the fake than the authentic product?

As with lower-priced whiskies from Japan, there are a ton of retailers online to choose from. Shop around and get a baseline price for the bottle you’re looking for. Many of these shops deliver too.

Just want a glass of your favorite Japanese whisky? Restaurants and bars typically offer more reliable access. Prices range wildly, of course. Let’s look at the previously cited 20% cost benchmark. If a 750ml bottle of whisky costs $150 wholesale, a 1.5-ounce serving would come out to $44.30. Don’t treat this number as gospel, because every business has different operating costs. However, this is a good starting point for value shoppers to consider.

Shopping for Luxury Japanese Whisky

Are you in the market for a big name brand like Yamazaki 18 or Hibiki 21? What about rarer, discontinued whiskies like Nikka Yoichi 15 or a Karuizawa? We have some advice for you as well.

There’s a big range of prices here. A product like Nikka’s Yoichi Apple Brandy Finish might only set you back $500. Paying under $10K for Yamazaki 25-year would be a steal. Want a Yamazaki 50-year? That will cost more than the average US home!

The fundamentals for smart shopping remain the same for whiskies below $10K. You’ll want to shop around more than ever. Use sites like Wine-Searcher, Drizly, or The Whisky Exchange to establish a baseline price for your desired whisky. Sometimes it’s best to wait.

If you can, keep an eye out for these whiskies in retail outlets in Japan. You can sometimes save $1000’s compared to prices in North America or the EU. You’ll still want to be patient, though.

Once you start looking for whiskies that are extremely rare, your bargain-hunting options will dwindle. Many of the rarest Japanese whiskies are only available through a few shops worldwide or at auction.

Collecting Rare and Expensive Whisky from Japan

Most Japanese whisky is not a collector’s item. Determining what is, and what is not collectible takes research. That said, there are some general indicators of what may become collectible.

There are a handful of brands that have the cache to move up in price. Yamazaki and Hibiki are the most obvious duo. Hakushu certainly belongs here as well. They’ve long been the value single malt from Suntory. But cuts to the Hakushu lineup have scared the market and is causing prices to rise.

Nikka’s Yoichi and Miyagikyo also have the prestige to be collectible. This is also true for most of the limited-release whiskies from Chichibu/Ichiro’s Malt. Lastly, whiskies from closed distilleries like Karuizawa, Kawasaki, and Hanyu are most-definitely collectible. Even if these brands return, you can’t replace the originals.

But the brand alone does not make a Japanese whisky a valuable commodity. Being discontinued, or the fear of it is usually the other side of the collectability equation.

As mentioned, Hakushu prices are on the rise after Suntory temporarily discontinued Hakushu 12. Enthusiasts of the 18-year have been scooping up that brand out of fear it will be next. This is speculative buying is happening with Hibiki and Yamazaki whiskies as well.

Other classics like Hibiki 12, the Nikka age statement whiskies, and the Karuizawa’s have already ceased production. These whiskies should continue to go up in value. At what rate is anyone’s guess though.

For fans of these whiskies, it’s easy to assume that this trend will continue. And for the near future, it probably will. However, the global success of Japanese whisky encouraged distilleries to increase production. At some point, the gains in supply will be felt. Though we still may have to wait a decade or more for some of the age-statements to potentially return.

If you’re targeting collectible whisky, it’s critically important that you research the market. The internet has opened up the inventory of millions of retail shops. Some of these may ship to you. Cast a wide net, determine your max price, and don’t be afraid to walk away.

Ready to find your next Japanese whisky?

Check out our list of the most common brands and producers.

What is Whisky?

To become an expert in Japanese whisky, you must understand the fundamentals of whisky.

The Definition of Whisky

Whisky has a few features that define it.

One such feature is that whisky is made from a fermented mash of cereal grains. Barley, corn, and rye are the most commonly used grains. Wheat, oats, rice, and other grains are also used, depending upon the local grains being grown. In most cases, malted barley is a key ingredient. Malt can break down the grains in a mash into a fermentable, sugary liquid.

Another defining feature of whisky is a bit more technical, though still important. Whisky will be distilled to less than 95% abv. This is so that it retains some of the characteristics of the base ingredients. Most whiskies won’t be distilled to this high of a proof, and many of the best will come of the still at around 70% abv or less.

A third and very important feature of whisky is barrel aging. You cannot make whisky without it. Most countries require a minimum of 2 or 3 years in wood. The interaction between liquor, barrel, and air give whisky its look and taste. You cannot make whisky without them.

Finally, most whiskies need to be bottled at a minimum strength of 40% abv.

Where Did Whisky Come From?

Whisky is a spirit of Celtic origin. It’s unclear whether it began in Scotland or Ireland, but it is clear that both places were involved. The Irish called it uisgebaugh, and the Scottish uisgebeathe— both translate to “water of life.” The first written record goes back to 1495.

This spirit eventually made it into England, where it was popularized. The English also Anglicized the name to whisky.

Japanese Whiskey or Whisky?

There is no universally correct answer. The Scottish, Canadians, and Japanese use the spelling whisky. The Irish use the spelling whiskey. In the United States, whiskey is the typical choice, but legally either spelling is allowed.

Common Types of Whisky

Here’s a short list of some of the common types of whisky being made.

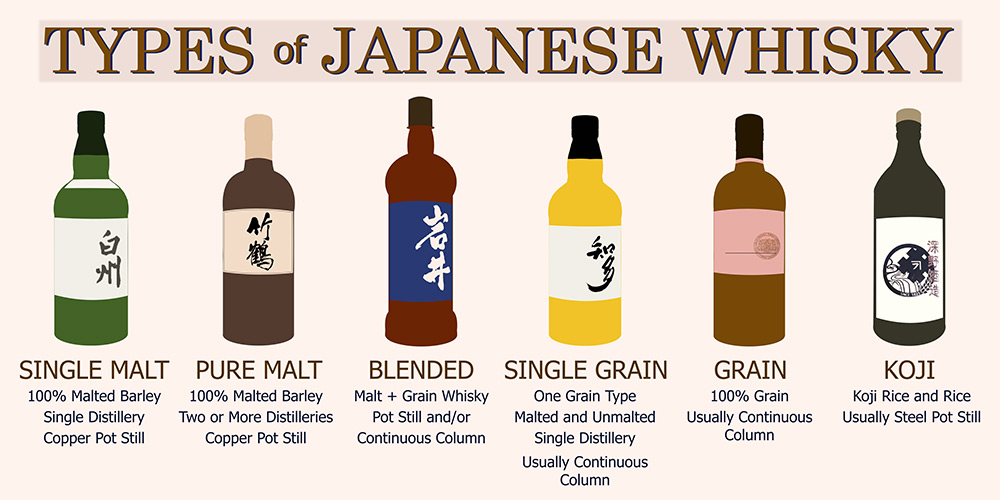

Single Malt

Single malt whisky is made at a single distillery, made from only a single type of malted grain. Usually, the malt is made from barley. Copper pot stills are also a common requirement.

Single malt whisky is a premium product. They are typically robust in body with a rich flavor profile.

Blended Malt

A blended malt is made when two or more malt whiskies from different distilleries are blended together. The flavor profile is similar to a single malt whisky. This style was often called vatted malt in the past. This is another type of whisky that is typically produced in pot stills.

Pure Malt

Pure malt whisky is a somewhat confusing category. A lot of single malt Scotch had been labeled as pure malt whisky in the past. The Japanese have taken the term and applied their own spin on it. In their case, pure malt whisky is often a blend of malt whiskies from different distilleries.

This would indicate that pure malt is the same as a blended malt, but there’s a catch. In Japan, distilleries are fiercely competitive and do not trade or use other distillery’s whiskies. A pure malt from Japan is a product of multiple distilleries but owned by the same company.

The most famous examples of this are Nikka’s Taketsuru Pure Malt whiskies. These 100% pot-distilled malt whiskies are a combination of two distilleries: Yoichi and Miyagikyo.

Single Grain

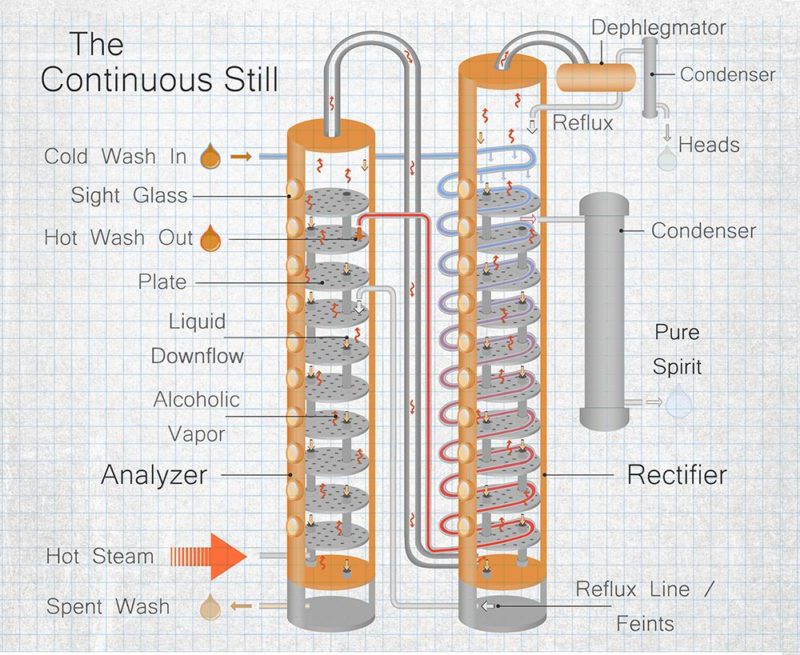

Single grain whisky is made at a single distillery, using only one type of grain. This grain can be a combination of malted and un-malted components. Single grains are usually made in a continuous still.

Blended Grain

Blended grain whiskies are a combination of two or more single grains. This is not a common style.

Grain

Grain whisky often ends up in blends, rather than being bottled on its own. Sometimes there is no malted barley used either. In this case, hydrolysis will be used instead.

Grain whisky is usually continuous column distilled to a high proof.

Blended

Blended whisky is a large category. Every whisky-producing country produces blended whisky, so there is no universal standard. That said, blended whisky is made by blending malt and grain whiskies. Usually, grain whisky dominates the blend, but there’s a lot of variability.

The above types of whisky are the most common. But there are many other types, depending on the country of origin. To see a full list, check this out.

Age Statement and NAS Whiskies

Most whisky-producing nations will require a minimum of two or three years in a barrel. The vast majority of whiskies will not list an age statement on the bottle. If they do, all whiskies used to make a product must be at least as old as the listed age. That means a bottle that’s a blend of 18-year old and 4-year old whiskies can only be labeled as a 4-year aged whisky.

Age statement whisky is common with Scotch and was once more common with Japanese whisky. Whisky without an age statement is often referred to as a non-age statement whisky or NAS.

Still want more whisky knowledge?

Learn the basics of whisky with our post From Grain to Barrel

Whisky Making: Production Overview

Now that you know the basics of whisky, are you ready to find out how it’s made? Below is an outline of the process. Each one of these steps has many variables that will affect the quality of the whisky being made.

Malting, Milling, and Mashing

Making whisky begins with the ingredients. The mash bill, or grain bill, is the blend of grains used in the recipe. Malted barley is typically among them because it contains enzymes that will break down the starch in other grains to more fermentable glucose.

To make malt, you have to sprout the grain. This triggers the formation of the enzymes. Before the grain is fully sprouted, it is then heated (kilned) to stop its growth. Kilning also roasts the malt, which changes its flavor and color.

Once you have malt, it’s time to mash. The malt and other grains are milled into grist. The grist is then steeped in hot water in a mash cooker. The hot water softens the grains, liquifies starch, and activates the enzymes in the malt. This sugary liquid is known as mash or wort.

Fermentation

Adding yeast to the sugary mash is needed to produce alcohol. The single cell fungus eats glucose and produces ethanol and CO2. This step happens in a washback or an open fermenter.

The fermented mash is usually between 8% and 14% abv. At this point, it’s now known as beer. Yes, beer. It does not contain hops, but is otherwise the same thing.

Distillation

Distillation is where the process of concentrating alcohol to the desired strength by separating out water and the other dissolved components. With this process, beer is turned into liquor.

This action takes place inside of a closed still, which is almost always made of copper. The quality of the distillate is largely influenced by this step. By selecting the best part of the distillation run, one can make pretty good whisky.

This is a complicated subject.

Go to The Fundamentals of Whisky Production to learn more.

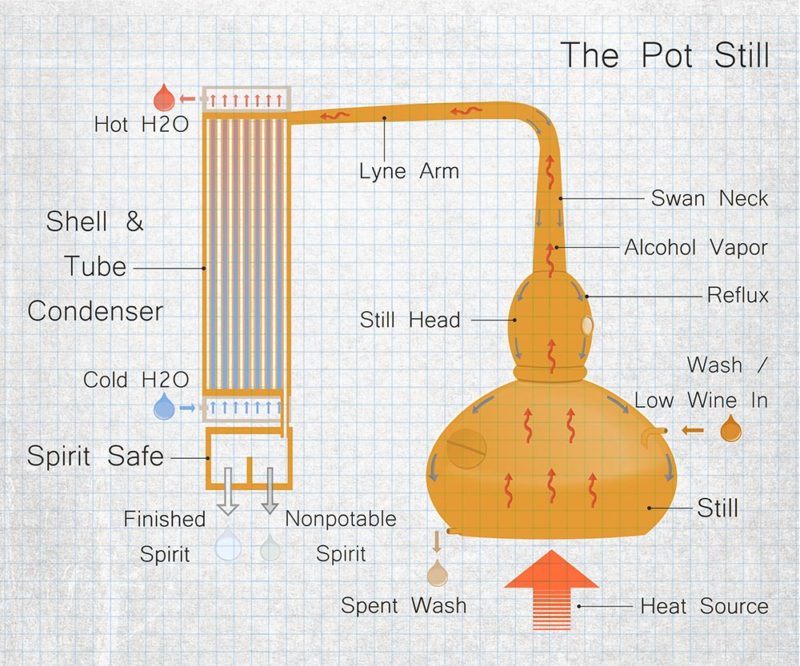

Types of Stills

A still is the structure where spirits are made. They are closed and allow the fermented liquid to be heated, and the alcoholic vapors to be collected at the top.

Stills for liquor production are almost always made of copper. This element effectively strips many harsh compounds (congeners) from the spirit. The more time the distilled alcohol solution comes into contact with copper, the lighter and smoother it will become.

The pot still and the continuous column are the two main types of alcohol stills.

The Copper Pot Still

The pot still is the older design and has countless variations. At its core, this still type uses a batch process. The first run will concentrate beer to a strength around 25% abv. This crude spirit, called low wines, is then re-distilled to a strength of about 55%-70% abv. The second distillation refines the low wines into a potable spirit.

Oftentimes, distillers will stop after this second distillation. A third distillation can be used as well. This tends to make the final spirit lighter in body and flavor.

You can make really high-quality whisky in a pot still. But using a batch process is inefficient. It takes more labor and time to make whisky this way.

The Continuous Column Still

The continuous column still was invented to increase the efficiency of the distillation process. Using one will produce a pure and light spirit. This is why it became the industry standard for making neutral spirits.

And continuous stills are used to make whisky too. That’s actually why it was invented. It’s a common practice for grain whiskies to be made in continuous stills. Using one will result in a lighter whisky, with fewer congeners. This means it will be less harsh but also have less character.

There is so much more to stills than this.

Learn more about the types of whisky stills now!

Cask Aging

Without cask-aging, you cannot make whisky. Spending time in an oak barrel changes a clear base spirit into a dark and complex whisky.

This evolution happen because of a number of factors.

Many of the principal flavors of whisky come from oak itself. Common tasting notes of vanilla, coconut, caramel, and smoke can be traced back to oak barrels. The type of oak used, how it was dried, how new it is, and how much the barrel is toasted are all significant variables.

The porous oak encourages oxygen contact and leads to a darker color, causes evaporation, and concentrates the whisky.

Types of Casks

There are a lot of different casks and barrels in use for making whisky. And when it comes to barrel types, a major consideration is the type of oak used.

American white oak is a common choice for whisky casks. It’s a sturdy wood and can be purchased for a low price. Characteristics of American oak include a loose grain, wider growth rings, and high tannins. Barrels made with it allow for more evaporation than European types.

Some markers American oak-aged whisky includes vanilla, cinnamon, coconut, dill, and brown sugar.

European oak is another common wood used for making casks. European types tend to be more porous and slower growing than American oak. They allow less evaporation to happen, which slows down the maturation process.

Euro oak is often associated with flavors like dark chocolate, savory spice, dried fruit, and coffee beans.

Japanese mizunara oak is all the rage these days, and it can command very high prices. This porous oak is leaky and difficult to work with. It had long been viewed as inferior to American and European oak. However, the flavors it delivers are highly sought-after.

Common tasting notes for mizunara include sandalwood, aloe wood (kyara), coconut, and honey.

Cask Finishing and Second Use Barrels

Whisky casks aren’t limited to simply the type of oak. Oftentimes, a cask used to age whisky will have held something else in the past. Whiskies may spend their whole lives in these used casks, or they may just rest in them briefly (cask finishing).

Ex-bourbon barrels are commonly used to age whisky. Bourbon regulations require new barrels, meaning there are lots of charred, spicy barrels available.

Casks used to age sherry are also frequently used, and are highly prized. Most sherry casks are ancient, and the wineries are not selling them. Instead, sherry casks come from specialists that season new barrels with sherry, before selling them to whisky producers.

Madeira, Port, and Sautenrnes barrels are less commonly used than sherry, but are still highly prized. Other casks types include rum, Tequila, shochu, wine, IPA, and even sake.

Climate and Aging Whisky

The final piece of the whisky-aging puzzle comes down to storage conditions. Climate has a dramatic effect on whisky maturation. Hot temperatures accelerate evaporation, for example.

Humidity will also affect what gets evaporated. High levels of moisture in the environment will promote the evaporation of alcohol more than water. This will lead to a slow decrease in alcohol content.

Dry conditions will encourage water to evaporate more easily than alcohol, which will increase alcohol concentration over time.

Either way, this loss of liquid from the barrel is called the angel’s share. The whisky that remains in the cask will continue to grow in intensity.

Finally, how the barrels are stored can have a big impact. Spacing in between barrels and how high they are stacked are significant variables. For example, a Scotch-style dunnage warehouse will result in less evaporation and slower maturation. Bourbon barrels are often stored in rackhouses up to 10 stories high. Temperatures at the top can be significantly higher than the bottom, which can accelerate maturation.

Aging Whisky in Japan

The climate of Japan is quite humid but ranges from cold to tropical depending upon the latitude. As discussed, humid climates will cause the alcohol component of whisky to evaporate more rapidly than the water. This results in a steady reduction of proof in most whiskies aging in Japan. Concentration continues to increase, however.

Temperature will have a large impact on the rate of maturity, as well. Whiskies aged in cold Hokkaido will develop more slowly than those that are aged in sub-tropical Kagoshima. Neither is superior to the other. Temperature is just another variable that impact whisky aged in different locations in Japan.

Do you want to learn more about how whisky casks?

Check out The Oak Barrel and Whisky Connection to level-up your whisky IQ!

Whisky Blending in Japan

Japanese whisky producers don’t work well together. This is a relic of the fiery competition between Masataka Taketsuru (Nikka) and Shinjiro Torii (Suntory).

In Scotland, whisky is broadly traded and sold to make blends of different distilleries. But the Japanese never figured this out.

Instead, Japanese whisky makers have mastered the art of blending in-house. Part of this equation is to use a variety of still designs, distillation techniques, and barrel types to produce a variety of styles in-house. Master blenders then combine the separate components to make very complex whisky.

But there is also another component to blending and Japanese whisky that is less savory.

Blending Imported Whisky with Japanese Whisky

We’ve discussed the underbelly of Japanese whisky earlier in this post, but it’s worth discussing here, as well. The Japanese whisky industry relies heavily upon imported whisky. And because Japanese producers don’t like to trade with one another, their blended whiskies regularly use these imports.

This practice goes back to the early days of Japanese whisky production and continues to this day. Within Japan, most entry-level domestic whiskies are almost entirely made up of bulk-purchased whisky from Scotland, Canada, and the United States.

Even some award-winning Japanese whiskies, like Nikka From the Barrel, rely upon imported whisky to produce their sophisticated blends.

There are signs that some producers in the industry are willing to change their ways. Chichibu and Mars recently released blended whiskies using some of the other producer’s distillate. We hope to see much more of this in the future.

Serving Japanese Whisky

There are many ways to utilize Japanese whisky. The most important consideration is your preference.

A splash of water or a single ice cube are general suggestions for sipping fine whisky. Lower quality brands may do better on the rocks or as a cocktail.

Using a larger ice cube has become very popular. Big cubes tend to melt slower and will significantly cool a whisky. But melting will still happen, so watch out for over-dilution.

Glassware

The type of glass you use will literally affect how a whisky tastes. Most larger glasses offer better control of aromatic intensity. The opposite is true of a small vessel such as a shot glass. With little headspace, it will be difficult to detect the aroma and flavors will seem lighter.

The ultimate whisky glass has a concave shape with a wide bowl and a narrower opening. This design will hold the aroma, allow you to swirl the whisky, and let you better assess the flavor profile.

Temperature

Nobody likes hot whisky. Alcohol can already burn, and warm temperatures accentuates that effect. That’s why we suggest a single ice cube with finer whiskies. This is particularly true if the bar is warm.

Sometimes, warm whisky is actually desirable. The addition of hot water can open up a whiskies aroma as well. And at the same time, the water dilutes the spirit to a more palatable alcohol content. This is really the same concept as oyuwari, the hot water and shochu mix that’s popular in Japan. And wouldn’t you know, it works really well with koji whisky.

Japanese Whisky Cocktails

There are a number of classic whisky cocktails where Japanese whisky will shine.

The Manhattan and Old Fashioned are excellent choices for mid-level whiskies. Both are adept at masking harsher flavors as well.

Other cocktails that translate well with Japanese whisky are the Penicillin, whisky sour, boulevardier, and the Sazerac. With these, the whisky can be hidden by the other ingredients, for better or worse.

The Japanese Whisky Highball

The classic Japanese whisky cocktail is the whisky highball. Chilled whisky, sparkling water, and ice are all you need. It’s a simple recipe, but we recommend expressing a lemon peel over the drink.

Check out our post about this classic Japanese whisky drink to get recipes and whisky recommendations.

Food Pairing with Japanese Whisky

Whisky is not often thought of when discussing food and beverage pairings. Traditionally, it’s held a place at the end of the dining experience. And it works really well with the food associated with stage of the meal.

Rich desserts are usually good alongside dessert. This is especially true if there are spice elements like cinnamon and vanilla. Caramelized desserts also tend to work well with whisky. Apple pie, pecan pie, creme brulee, and anything covered in ganache are all going to work with most whiskies.

Cheese and whisky is another good end of meal combo. Smokier Japanese whiskies like Yoichi and Hakushu are great with blue cheese. Fruitier brands like Yamazaki and Miyagikyo pair well with softer, bloomy rind cheeses like Mothais a la Feuille.

Scotch and oysters are a classic pairing that can work with Japanese whiskies too. This is especially true with whiskies made with peated malt. Yoichi and Hakushu fit the bill again.

If you’re looking to have whisky throughout a meal, mizuwari is a great option. By adding water to your whisky, you can bring down the flavor to a more food-friendly level. The caramelized, grainy, and mineral characteristics in many whiskies can match many types of food. Grilled beef and whisky is a pairing that can really work.

Japanese Whisky Brands and Producers

Learn about the most important brands of Japanese whisky.

Suntory Whisky

The brands and distilleries from Suntory are legendary: Yamazaki, Hakushu, and Hibiki. Suntory would produce the first authentic Japanese whisky. They would popularize whisky in Japan, and later abroad. Now their whiskies are easily some of the world’s most wanted. And they earned it.

Suntory started with Shinjiro Torii and his vision to make authentic Japanese whisky. Torii turned Suntory into a giant with a lifetime of savvy decision-making. One of his most fateful moves was to hire Masataka Taketsuru to help develop Yamazaki. The distillery was launched in 1923.

Taketsuru would go on the found Nikka, but his expertise surely helped Yamazaki become a success.

The Yamazaki whiskies are now among the world’s elite. Using a variety of pot stills, this distillery produces a variety of malt whisky profiles. Direct fire is sometimes used to produce a roasted and robust character. Yamazaki whiskies also see a large variety of barrel types for added complexity.

In 1972, the Chita grain whisky distillery was completed. The year after that the Hakushu was launched. The Chita’s whiskies are mostly used for Suntory’s blends. This includes the uber-famous Hibiki.

The Hakushu, like Yamazaki, also utilizes a variety of pot stills to make malt whisky. Hakushu whiskies tend to use more peated malt than Yamazaki. The finish of their single malt is often crisper as well.

There’s too much to write about Suntory here.

Take your Suntory, Yamazaki, Hakushu, and Hibiki whisky knowledge to the next level!

Nikka Whisky

Nikka is one of the two iconic producers of Japanese whisky. The company founded by Masataka Taketsuru would go on to rival Suntory in prestige. Their whiskies are in equally high demand, which is no small achievement.

The Yoichi Distillery in Hokkaido was Nikka’s first. Taketsuru founded in 1934. He chose the frigid and maritime location for its similarities to Scotland. From the start, Yoichi pot stills have produced malt whisky in smoky Scotch-inspired style. Similar to Yamazaki, Yoichi stills are also often direct-fired for a rich character.

Nikka expanded its range in 1969 with the Miyagikyo Distillery. This time both pot stills and a pair of dual-column continuous stills were used. The latter type of skill is commonly referred to as a Coffey still.

Having multiple types of stills allows Miyagikyo to produce a large variety of whisky profiles. Bottles released under the Miyagikyo brand are usually single malts.

Nikka also produced a big hit with their Taketsuru line of pure malt whiskies. This brand uses malts from both Yoichi and Miyagikyo.

Nikka is another BIG subject.

Check out our informative Nikka whisky guide to learn more now!

Mars – Hombo Shuzo

Mars whisky is a favorite of many Japanese whisky enthusiasts. This has a lot to do with their high quality and reasonable prices.

Hombo Shuzo (本坊酒造) is based out of Kagoshima and produces Mars Whisky. They started out as a Satsuma shochu producer— a practice they continue.

The Mars Shinshu Distillery was built under the shadow of Mount Komagatake in 1984. They shut down production during the Japanese whisky bust but resumed operations in 2011.

Iwai and Iwai Tradition are the flagship export brands from Mars. Both are blended pot still whiskies made with malted barley and corn. The standard Iwai is mostly corn, while Tradition is malt-dominant. Each is affordable and excellent in cocktails.

Mars Iwai 45 is a new, 90 proof version of the regular Iwai.

Mars Komagatake brand is a line of single malts released in small quantities. Japanese whisky junkies should seek these bottles out. However, they are a large step up in price over the Iwai labels.

The Mars Tsuniki (津貫) whisky distillery was completed in 2016 and has expanded their range of products. Check out this interesting Whisky Magazine article about Tsunuki and Mars.

Akashi – Eigashima Shuzo

Akashi whisky is a solid brand to know. Their homey White Oak Distillery houses a pair of copper pots stills and makes some quality malt and grain whisky.

In North America, Akashi Blended and Akashi Single Malt are the two most accessible brands. Most of the other Akashi whiskies are produced in very small quantities.

The maker of Akashi, Eigashima Shuzo, was the first licensed whisky distillery in Japan. They did not use it at the time, however.

Check out our post on Akashi Whisky and Eigashima Shuzo to learn more about their products.

Akkeshi

The Akkeshi Distillery is a new producer located in rural Akkeshi, Hokkaido. They began distillation operations in 2016.

Akkeshi aims to produce whisky with a Islay Scotch-like character.

These whiskies are still young but have great promise.

Kurayoshi – Matsui Distillery

Kurayoshi is one of the more infamous upstart Japanese whisky brands. Their first releases were age-statement single malt whiskies produced in Scotland but sold as Japanese whisky. They used this capital to create their own distillery.

Their range now includes Matsui and Tottori brands whiskies.

Kirin Whisky – Fuji Gotemba

Fuji Gotemba is a whisky distillery owned by Kirin. It’s located on the slopes of Mount Fuji in Shizuoka, Japan. While this is a major producer of Japanese whisky, their products aren’t currently available in the United States.

The distillery is fitted with four copper pot stills. They make both single malt and grain whiskies, as well as blends.

Helios

Helios is a large liquor producer (and beer brewer) from Okinawa. They make a variety of spirits including rum, Awamori, habushu, and whisky.

Their product Kura The Whisky uses imported American white oak aged whisky that they finish in their rum casks.

Togouchi – Sakuroa Brewery and Distillery

The Sakurao Brewery and Distillery of Hiroshima produces a variety of alcoholic beverages including sake, umeshu, gin, and whisky. Well, they don’t make the whisky, but they do age it a little in their subterranean warehouse.

Togouchi uses mildly peated Scotch for their whiskies. They will be releasing their first whisky produced in-house, a three-year-aged single malt, in the summer of 2021.

Fukano

Fukano is a rice shochu distiller from Hitoyoshi, Kumamoto. This region is famed for its Kuma shochu.

Some of their honkaku (once distilled), genshu (undiluted) Kuma-jochu got placed into wood casks and aged for a long period of time. The resulting dark spirit looked and tasted remarkably like whisky. Eventually, it found its way into the United States bottled as rice whisky.

Fukano whisky is light, fruity, and savory. Oak spice is restrained and the finish is incredibly mild and smooth.

Even though Fukano whisky is technically over-aged shochu, it’s pretty good stuff. And it’s made in Japan. We’re big fans.

Ohishi

Ohishi is another Kumamoto rice shochu producer with a similar backstory. Their koji whiskies tend to be a little darker and heavier than Fukano’s but are still relatively light and fruity compared to traditional whisky.

Follow the Japanese Bar on Social Media

Connect with our latest posts, the newest Japanese beverage info, and get exclusive promotional offers. Level-up your Japanese whiskey IQ!