Last Updated 1/26/2021

Rice is one of the essential ingredients in sake. Many types exist just for brewing sake. These specialty rice strains, called sakamai (酒米), are often compared to grapes for wine.

But is sake rice really that important?

This page will answer the most important questions about sake rice. You’ll learn about what makes sake rice unique. We’ll also cover the most important types of sakamai used to brew sake.

Major Types of Sakamai

What is Sake Rice?

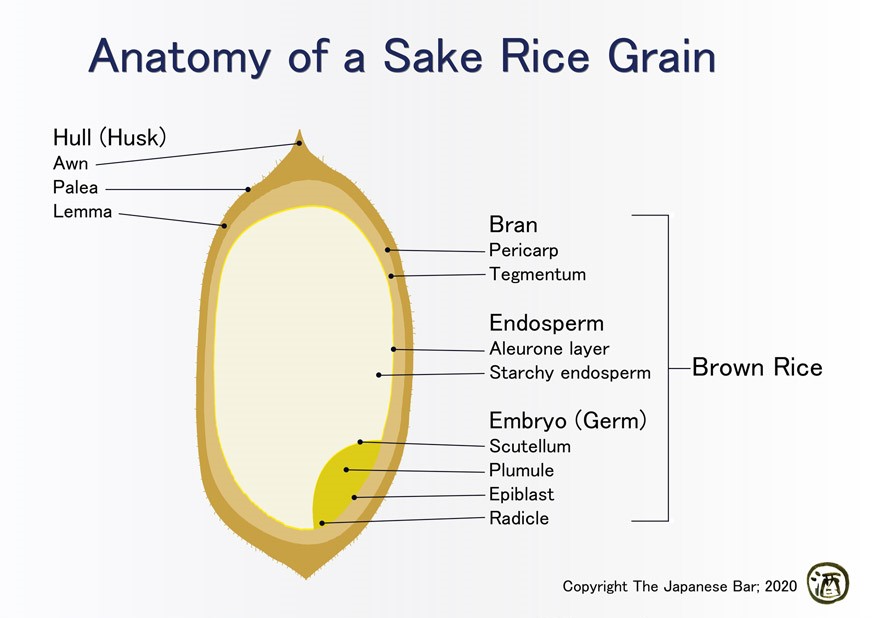

Sake rice is any strain of rice that’s used to make sake. Sakamai is the term for this broad category. Most sake rice is short-grain japonica. Ideally, it will have a large starchy core (shinpaku). This shinpaku is what koji mold need to produce fermentable sugars.

Low levels of protein are another desirable trait for sake rice. Additionally, good sake rice will have good water absorption, mill without breaking, and is koji-friendly.

There are two types of sakamai. Shuzokotekimai (酒造好適米) is a variety that is used only for brewing sake. These types tend to have large grains with a starchy core. The most famous types of sake rice fall into this category.

Famous examples of shuzokotekimai (shuu zoh koh tek kii my) include Yamada Nishiki, Omachi, and Gohyakumangoku.

Table rice can be used for sake brewing, as well. This is the other type of sakamai. Using table rice has some advantages. Primarily, a lot of it is grown, which means it is usually much cheaper.

Popular types of table rice that are used to brew sake include Koshihikari and Hitomebore.

Where Does Sake Rice Come From?

All rice cultivars originated from heirloom (wild) strains. Today, there are a handful of heirloom sake rice strains still in use. And there have been impressive efforts to bring back some of the ancient grains.

Most sakamai in use are not heirloom strains, however. They are the result of the intentional selection and crossing of varietals by regional agricultural institutions and farmers.

It is often a local effort to create new strains that are locally adapted. There’s also a desire to promote regional character. Today, most prefectures have their own sakamai varietals.

Many believe the best sakamai are grown in the west (Hyogo, Okayama, and Hiroshima). However, there is some elite sake rice that hails from the north and east of Japan.

Growing Sake Rice

What makes good table rice and what makes good rice for sake brewing are two completely different things.

Fat, heavy grains can weigh-down a rice plant. Additionally, sake rice is often taller than table rice cultivars. This makes it susceptible to wind damage (lodging). If the plant falls over, it’s dead. Shelter from wind is an important consideration for a sake rice paddy.

The specialty nature of sake rice grains means they typically cost around twice as much as table rice varietals. Overall, shuzokotekimai only accounts for about 1% of the total rice production in Japan.

Most sake rice varietals use wetland cultivation. This means the field is flooded either with rain or by irrigation.

Milling Sake Rice

Raw rice is not ideal for brewing quality sake. Milling is required to remove the outer hull and at least some of the bran.

Generally speaking, the more a rice grain is milled (polished), the fruitier and smoother the final sake will be. This is incredibly important.

So important, in fact, that sake is graded by the amount of rice polishing that occurs.

You can explore the different sake grades on this post.

The Top Sake Rice Types by Production Volume

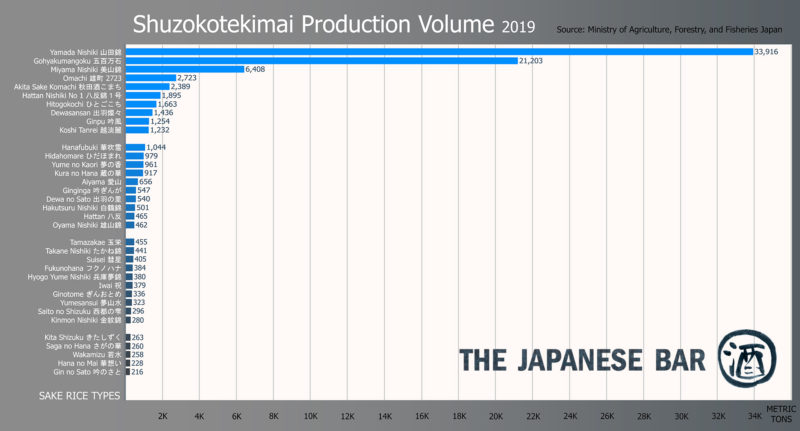

By volume and popularity, Hyogo’s Yamada Nishiki rice is the king.

2019 tallied nearly 34,000 metric tons.

The only sake rice that’s close is Gohyakumangoku. The harvest in 2019 was around 21,000 tons. This Niigata creation is not as flashy as Yamada Nishiki, but brewers love it.

Meanwhile, the heirloom Omachi rice strain may be the most revered. It ranks a distant fourth in production volume for sake rice with 2,723 tons. The sake made with it is highly sought-after. Omachi is one of the ancestors of Yamada Nishiki, Gohyakumangoku, and a bunch of other important sake rice types.

Rounding out the top four is Miyama Nishiki. It’s a workhorse shuzokotekimai in northern Japan and Nagano. Japan had a harvest of 6,408 tons in 2019, comfortably third in sake rice production.

The 4 Most Important Types of Sake Rice

Many interesting sake rice strains are used to make quality sake. These are the most important in terms of production volume and prestige.

Yamada Nishiki 山田錦: The King of Sake Rice

Sake made with Yamada Nishiki rice tends to be fragrant, fruity, elegant, and complex. It also polishes extremely well making it adept at making light and fruity ginjo-shu.

Omachi 雄町

Sake made with Omachi rice tends to be mildly aromatic, earthy, mellow, rich, and complex. An herbal quality is typically present. Omachi is a very old, heirloom sake rice strain. It has been used to cultivate many of the sake world’s most famous rice types. But in its original form, it has attained god-like status.

Gohyakumangoku 五百万石

Gohyakumangoku generally produces compact, clean, and light sake. Aromatics are often subdued, though yeast largely determines this feature. Gohyakumangoku is a relatively cold hardy sake rice type. Its widespread use is a testament to its toji-friendly nature.

Miyama Nishiki 美山錦

Sake made with Miyama Nishiki tends to have a ricey, grainy profile with muted aromatics, and often a mild sweetness. The rice-like, textured profile can be attributed somewhat to the grain’s moderate (for sakamai) shinkpaku levels.

Major Sake Rice from Northern Japan

In northern Japan, a growing number of localized sake strains are becoming available to brewers. These varieties are better adapted to a cooler, shorter growing season.

Dewasansan 出羽燦々

Sake made from Dewa San San is typically moderately fragrant, often more sweet than dry, and typically complex. Can range from fruity to earthy. This Yamagata-only sake rice varietal was originally crossed from Hanafubuki and Miyama Nishiki. In 2019, 1436 metric tons of Dewasansan was harvested– ranking 8th in overall Japanese shuzokotekimai production.

Kame no O 亀の尾

Sake made from Kame no O rice often have subdued aromatic intensity, but a rich, citrusy flavor profile. It tends toward the dry side and is often earthy with umami that lingers on the palate. Acidity can be elevated and features sour cream or yogurt notes. Kame no O 亀の尾 was discovered in Yamagata around 1900, and quickly became widespread due to its quality and its hardiness to cold.

Ginpu 吟風

Ginpu is Hokkaido’s signature sake rice. It produces a sake that is typically (but not always) a touch sweet with steamed white rice notes. Can range from light to big-bodied, but most examples are on the lighter side. Despite the lightness of body– this is a sake grain that is still capable of producing rich flavor profiles.

Akita Sake Komachi 秋田酒こまち

Developed in Akita in 1998, Akita Sake Komachi 秋田酒こまち has rapidly become the prefecture’s most popular sakamai for ginjo-shu. Because of elevated glucose levels, much of the sake made from Akita Sake Komachi leans toward the sweeter side. There is also often a spicy quality to this sake, alongside a whole fruit basket of tasting descriptors.

Ginginga 吟ぎんが

Sake made with Ginginga can have a grainy umami quality. But it is also typically light with a clean and refreshing finish. Adding to its complexity, Ginginga can display a diverse array of fruity notes too– particularly when paired with local Iwate yeast and/or ginjo brewing techniques. All this can lead to a lot of variation in profiles of sake rewed with Ginginga. It’s best you go out and sample as many as you can!

Major Sake Rice from South and Central Japan

The southern portion of Japan, from Kanto southwest to Kyushu is home to some of the classic sake rice strains. And while Yamada Nishiki and Omachi hog much of the spotlight, there are quite a few others that deserve attention.

Watari Bune 渡舟

The heirloom Watari Bune sake rice tends to produce aromatic, full-bodied, layered, and fresh sake. Citrus, flowers, and streamed rice are just a few common descriptors. This sake rice was once very popular, but Wataribune 渡舟 died out for half a century. It is believed to be a pure-line selection of Omachi rice that took well in the Kanto region.

Tamazakae 玉栄

Sake made with Tamazakae tends to be soft-textured, rich in flavor, somewhat savory, smooth, and complex. This is a popular sake rice in its native Shiga and Torrori. Tamazakae is a cross between Yamazakae and Shirakiku. It’s tricky to grow, with very large grains, moderate in shinpaku (≈25-60%), and relatively low in protein. Tamazake is also tall, with a stalk height around three feet.

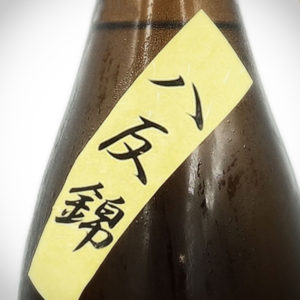

Hattan Nishiki 八反錦

Sake made with Hattan Nishiki tends to be medium-bodied, earthy, soft-textured and can display a varying degree of dryness. Born in Hiroshima in the 1970s, Hattan Nishiki 八反錦 sake rice is a cross between Hattan-35-go and Akitsuho. It took about ten years before it was ready for the market. Today, it falls within the top ten in sakamai production volume in Japan.

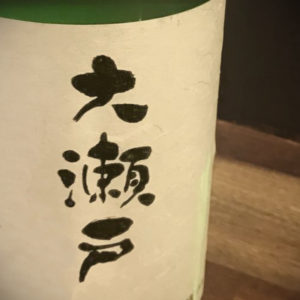

Oseto 大瀬戸

Sake made with Oseto is characterful and high in umami. Aromatics are restrained, and the finish is clean and crisp. It is sometimes spelled Ohseto or Ooseto when Romanized. The Oseto sakamai is grown primarily in Kagawa, but also elsewhere on Shikoku island. Its grains are relatively small and high in protein. It makes up for the small grain size with high yields and its dry (not sticky) nature. Koji happily takes to Oseto rice.

Other Important Rice Strains

At the moment, there are a lot of sake rice types that don’t have their own page on this site. This is a shame, but for now, basic info about many of them will appear below in alphabetical order.

Aiyama 愛山

Aiyama is a promising sake rice grown only in Hyogo. Cultivation of it began in 1949. It typically makes full-bodied sake that’s balanced between umami and fruit. Acidity is often elevated.

Production volume of brown rice hit 656 metric tons in 2019. An astounding 43 tons of this was certified top-quality Tokujo (特上) grade, with an equally impressive 265 tons of it qualifying as the next best Tokuto (特等) grade of quality.

For a long time, Aiyama was quietly a Kenbishi-only rice. The Great Hanshin Earthquake of 1995 destroyed most of their brewery, and they were unable to purchase this rice from the farmers that grew it for them. It instead was eagerly used at Takagi Shuzo, maker of famed Juyondai. The cat was out of the bag, and this excellent shuzokoutekimai hit the open market.

Aiyama is a cross of Aifune 117 (愛船117) and Yamao 67 (山雄67). The lineage of these parent strains is impressive and includes Omachi, the pure-line strain Funaki Omachi (船木雄町), and Yamada Nishiki.

Popular Sake Brewed with Aiyama Rice

Aiyama

Junmai Ginjo

Aiyama

Junmai Daiginjo

Dewa no Sato 出羽の里

Dewa no Sato tends to produce clean-flavored sake (low amino acid), regardless of the milling rate. It is, however, susceptible to cracking and not suited for over-polishing.

This shuzokotekimai was created by the Yamagata Industrial Technology Center. It is a cross between Ginfubuki and Dewasansan. This means it’s a progeny of Yamada Nishiki, Tamazakae, Miyama Nishiki, and Hanafubuki– not bad!

It was officially adopted in 2004. The goal was to develop a rice type that was both high quality, but also very inexpensive to produce. It is extremely cold-resistant and is short– making it more wind-resistant. Dewa no Sato has large grains with ample shinpaku.

Dewa no Sato ranked 17th in total sake rice production in 2019 with 540 metric tons produced, and all of it was in Yamagata. It’s also another Yamagata sakamai with its own theme song.

Popular Sake Brewed with Dewa no Sato Rice

“Dewa no Sato”

Junmai

Ginfubuki 吟吹雪

Ginfubuki is a Shiga sake rice type registered by farmers in 1999. It is grown nowhere else with production on the rise. It often makes soft-textured sake and is favored in the region for brewing ginjo-shu.

Ginfubuki is a cross between Yamada Nishiki and the respected Shiga rice Tamazakae. Both have Omachi in their DNA. It’s not as tall as Yamada Nishiki with a lower risk of lodging and slightly higher yields. Ginfubuki also has more shinpaku than Tamazakae. It’s therefore a recommended sakamai for the prefecture.

240 tons were harvested in 2019 with an impressive 60 tons grading as Tokuto 特等 (“Special Quality”). That’s still not a lot of volume overall, so examples may be hard to come by.

Popular Sake Brewed with Ginfubuki Rice

“The Warrior’s Blend” Ginfubuki

Junmai Ginjo

Ginnosei 吟の精

Ginnosei is a sakamai exclusively from Akita. It is a cross of Aikawa No.1 (合川1号) and Autumn 53 (秋系53) and was first recommended for Akita rice growers in 1992. The majority is grown in the flat area in the southeast of the prefecture.

Ginnosei has large protein-rich grains with very little shinpaku. The lack of shinpaku could be an issue, but Ginnosei is easily milled without breaking. This fact, plus the large grains, means that it is still great rice for producing ginjo-shu.

Popular Sake Brewed with Ginnosei Rice

“Heaven’s Door”

Tokubetsu Junmai

Ginotome ぎんおとめ

Ginotome is an Iwate sake rice that matures early in the cold climate. It was developed as an alternative to Miyama Nishiki. It’s particularly popular around Iwate-gun (岩手郡). Ginotome has large grains, but is low on shinpaku, and is typically used on earthier grades like Junmai and Honjozo. It behaves similarly to Miyama Nishiki in the brewery.

Ginotome was developed by the former Iwate Prefectural Agriculture Experiment Station in 1990 and has been encouraged since 2000. It’s a cross of Akita Sake No44 (秋田酒44号) and Kokoromachi (こころまち), which means there’s Yamada Nishiki ancestry.

Ginotome experiences fast growth and early maturity– a good thing in Iwate. Disease resistance is strong and lodging resistance is moderate. Yields are high with consistent quality.

This sake grain is growing in popularity within Iwate with 336 tons produced in 2019.

Popular Sake Brewed with Ginotome Rice

“Southern Beauty”

Tokubetsu Junmai

“Southern Beauty”

Daiginjo

Goriki 強力

The Goriki shuzokoutekimai tends to make sake that has a muted aroma and is rich, spicy, and fresh on the palate. Its grains are very hard and polish well without cracking, albeit slowly. This density has some drawbacks in the brewery. The grain doesn’t dissolve easily and yields a lot of sediment. Alcohol conversion is relatively inefficient. This limits Goriki to craft brewing.

Goriki is a Tottori-only rice strain with a meager 113 metric tons produced in 2019. That’s not much by sake rice standards, but that amount is double the 2014 volume.

Goriki once had two popular strains: No.1– which was tasty, and No.2– which was fatter and suited for sake brewing. At one time, a third of Tottori’s rice paddies grew the grain. But it was easily lodged with low yields and died out around 1954. The Number 2 strain was revived in the late 1980s, and now Goriki is utilized by a handful of Tottori breweries. The production of this rice type is strictly controlled due to its ease of mutation.

Popular Sake Brewed with Goriki Rice

Goriki

Junmai Ginjo

Hanafubuki 華吹雪

Hanafubuki is a cold-climate sake rice type originating from Aomori in northern Japan. It has some of the largest grains that exist, albeit with modest shinpaku levels. It tends to make rich-flavored sake that is refreshing and clean.

Hanafubuki production volume hit 1044 metric tons in 2019– the 11th most among Japanese shuzokotekimai. The vast majority is from Aomori and of noteworthy quality. The rest comes from Fukushima plus trace amounts from Akita. Hanafubuki resulted from a Okuhomare (おくほまれ) and Fukei No. 103 (ふ系103号) cross, with Okuhomare having Yamada Nishiki roots.

Popular Sake Brewed with Hanafubuki Rice

Hanafubuki

Junmai Daiginjo

Hanafubuki

Tokubetsu Junmai

Hakutsuru Nishiki 白鶴錦

Hakutsuru Nishiki is the namesake sake rice varietal from the Hakutsuru Sake Brewery of Higashinada, Hyogo. It took 10 years of development after crossing Yamadaho and Tankan Wataribune. This famous pairing hadn’t been done in over 70 years. So why go through the trouble of re-creating Yamada Nishiki?

Smart branding aside, Yamada Nishiki came to be from a selection of particularly desirable plants over the course of many years. Had the selections been different, the resulting rice characteristics of Yamada Nishiki would have been different. And after so many decades of use, there is bound to be a lot of local variations and diversity of Yamada Nishiki– not all of it for the better. Hakutsuru Nishiki is a purer (fresher) and a unique selection of the sake world-famous love affair. Though it’s obviously close, it’s not the same rice.

Unsurprisingly, Hakutsuru Nishiki is catching on. In 2019, over 500 metric tons were produced. Most of this was in Hyogo, but some of it in Yamaguchi. The volume will probably continue to rise. Hakutsuru Nishiki has even larger grains and more shinpaku than its sibling, and it’s shorter and less prone to lodging.

Popular Sake Brewed with Hakutsuru Nishiki Rice

Hakutsuru Nishiki

Junmai Daiginjo

Hakutsuru Nishiki

Junmai Daiginjo

Hattan 八反

Hattan, or Hiroshima Hattan, is sake rice type that often makes fragrant, light, and mildly savory sake. It has very large grains with a lot of shinpaku– but this shinpaku is fragile and breaks easily. This limits Hiroshima Hattan’s milling ability, and so it’s hard to find as has higher-grade sake or in a 100% varietal form. The fragile shinpaku isn’t the end of the world, as it still dissolves well and makes a nice home for koji to spread.

Hiroshima Hattan is an older variety, presumably a pure line selection of Hattanso 八反草– but I cannot confirm this. In 2019, 465 metric tons were produced. A staggering 85% of that was 2nd best Tokuto (特等) grade quality. Hattan produces consistently uniform, large grains of consistent quality.

Popular Sake Brewed with Hiroshima Hattan Rice

Hiroshima Hattan

Ginjo

“Happy Bride”

KomeKome

Hidahomare 飛騨誉

Hidahomare is a sake rice from Gifu that makes complex sake with a touch of acidity and bitterness, balanced between sweet and dry. It’s often used to make ginjo-shu due to its large starchy grains. Tropical fruit notes are common.

Hidahomare was first cultivated in 1972 by the Gifu Agriculture Experiment Station. It was officially registered in 1982. Hidahomare is a cross of Hidaminori ひだみのり and Fukunohana フクノハナ with Fukunishiki フクニシキ. It has grains that are high in shinpaku and low in starch.

The year 2019 saw a harvest of 979 metric tons of Hidahomare– all in Gifu. That ranked 12th overall for sake rice production in Japan. An outstanding 450 tons of this was graded Tokuto (特等 “Special Quality”). Overall, this is definitely a shuzokotekimai to look out for.

Popular Sake Brewed with Hidahomare Rice

Hidahomare

Junmai Ginjo

Koshu

Daiginjo

Hitogokochi ひとごこち

Hitogokochi makes lighter and smooth sake. A range of flavor profiles are possible as it polishes well to about 50%. Still, it’s often used for kakemai.

This sake rice was born in Nagano and registered in 1995. The idea was to create a rice that compared favorably to Miyama Nishiki and its high protein, less ginjo-friendly characteristics. Hitogokochi largely achieves this and its popularity has increased. 2019 saw an impressive harvest of 1663 metric tons– ranking 7th in total Japanese shuzokoutekimai production. This was up from only 468 tons in 2014.

Hitogokochi is a cross of Shirotae Nishiki 白妙錦 and Shinko No 444 (信交444号). This means it has Tamazakae and Koshihikari in its ancestry. It has large grains that polish well. There are high shinpaku levels and little protein. The vast majority is grown in Nagano with the remaining coming from Yamanashi and Tochigi.

Popular Sake Brewed with Hitogokochi Rice

Muroka Genshu

Junmai

Hyogo Kita Nishiki 兵庫北錦

Hyogo Kitanishiki is an extremely high-quality sake rice type. It’s grown only in Hyogo– mostly in the Tamba (丹波) and Tajima (但馬) regions in the north. Sake brewed with it is said to combine the fruity, herbal qualities of Omachi, with the elegance and structure of Yamada Nishiki. Hyogo Kitanishiki has very large grains with ample shinpaku. It mills and brews well– so brewers like it. However, it is quite difficult to grow.

In 1974, Hyogo Kita Nishiki was first cultivated from a cross of Nada Hikari (なだひかり) and Gohyakumangoku (五百万石). This equates to Yamada Nishiki and Omachi ancestry. Kitanishiki was registered in 1987. As of 2019, 302 metric tons were produced. That’s up from 190 tons in 2014.

Popular Sake Brewed with Kita Nishiki Rice

Hyogo Kitanishiki

Junmai

Rojoh Hana Ari Tohka

Junmai Daiginjo

Hyogo Yume Nishiki 兵庫夢錦

Hyogo Yume Nishiki is a quality shuzokotekimai that has huge grains loaded with shinpaku. The sake it makes is typically dry with a refreshing finish. It’s often used as kakemai with Yamada Nishiki being used for koji.

Hyogo Yume Nishiki was first cultivated in 1977. It’s a cross of F2 Kikusakae (菊栄) and Yamada Nishiki (山田錦) with Hyogokei No. 23 (兵系23号). F2 means it was the second generation of this cross used as the selection. Kikusakae is itself a cross of Hyogo Omachi (兵庫雄町– an Omachi hybrid) and Kikusui (菊水), which has pure Omachi roots. That’s a nerdy way of calling Hyogo Yume Nishiki a thoroughbred sake rice.

In 2019, 380 tons of Hyogo Yume Nishiki were produced. Volume is on the decline with production of Hyogo Kita Nishiki taking up some of that space. This is in spite of the rice’s high yields, disease-resistance, solid lodging resistance, and early maturity. About 10% of the Hyogo Yumenishiki grown has been outstanding– ranked top-tier Tokujo (特上 “Extra Special”) and next-best Tokuto (特等 “Special Quality”). However, about half of the production volume is of lower grade with smaller grains and more inconsistent quality.

Popular Sake Brewed with Hyogo Yume Nishiki Rice

“Kaede no Shizuku

Junmai Ginjyo

Iwai 祝

Iwai is a classic sake rice from Kyoto. It tends to produce an elegantly fragrant and mellow sake with a soft texture. A ricey character is typical. Iwai has a lot of shinpaku and little protein within an average sized sakamai grain. This works well if you want to brew ginjo-shu.

But Iwai has a couple of issues that limit its production and availability. It’s a tall plant, and even for its height, it’s susceptible to catastrophic wind damage. Rain compounds this risk. Once some Iwai is harvested and milled to make some excellent ginjo-shu, there’s another catch: it dissolves easily during moromi and is an inefficient producer of alcohol. Iwai’s ease of lodging and its inefficiency in the brewery adds to the cost and scarcity of a pretty exciting sake rice type.

Iwai is a relatively pure rice strain with a small family tree. It was first cultivated in 1933 in the Tango (丹後) Branch of the Kyoto Prefectural Agricultural Experiment Station– the result of a pure-line selection of Nojoho (野条穂). It is still primarily grown within the Tango and the Tamba (丹波) regions of Kyoto prefecture. Its use died out by 1973 for a couple of decades.

In 2019, 379 metric tons of Iwai were produced, entirely within Kyoto. That ranked 26th among sake rice in Japan. Production volume is trending up over the last handful of years due to efforts to improve cultivation techniques.

Popular Sake Brewed with Iwai Rice

Iwai

Junmai Ginjo

Iwai

Junmai Ginjo

Kan no Mai 神の舞

Kan no Mai is a sake rice first cultivated in Shimane and grown nowhere else. Sake made with it tends to have a textural combo of soft and compact plus a mellow character. Kan no Mai brews a lot like the legendary Gohyakumangoku and yields better and more consistently in the cooler mountainous interior of Shimane.

Gohyakumangoku is one of the parents of Kan no Mai, with the other being Miyama Nishiki. Production volume of Kan no Mai has stayed relatively low since it was registered in 2000. 2019 saw 65 tons produced– some of that as high-quality Tokuto (特等 “Special Quality”) grade.

Popular Sake Brewed with Kan no Mai Rice

“Dance of Discovery”

Junmai

O-karakuchi

Junmai

Koshihikari 越光, こしひかり, コシヒカリ

Koshihikari is arguably Japan’s favorite rice. It’s sticky texture and mild, sweet flavor have been highly prized since the 1950’s. And indeed, when it’s used to brew sake, it will often have some sweetness and a mellow character. Koshihikari also ages well. Balanced sweetness, acidity, and umami can develop with time if aged properly. Not bad for a table rice cultivar with small grains and little shinpaku.

A staggering 1.4 million metric tons of Koshihikari was produced in 2019 across 44 prefectures. This is in spite of the fact that it’s a tall plant with feeble lodging and blast resistance. It was born out of the Hokuriku region (Niigata, Fukui), a cross of the popular, cold-resistant Norin 1 (農林1号) and blast-resistant Norin 22 (農林22号). Norin 1 has Kame no O roots.

Not all Koshihikari is the same. In order to combat some of the cultivar’s poor blast resistance, many crosses and selections have been made of the original for a more user-friendly plant. A multitude of Koshihikari BL (blast resistant line) cultivars exist. Sasa Nishiki (ササニシキ) is probably the most well-known and respected of these in the sake world. But overall, they’re not quite as fine as the original Classic Koshihikari (クラシックコシヒカリ).

Only about 1-2% of Koshihikari is this superior type. It has a sweeter taste and makes a more fragrant and rich-flavored sake. It’s grown on steeper slopes with large diurnal temperature fluctuations. The terrain demands farming by hand and produces lower yields.

Popular Sake Brewed with Koshihikari Rice

Organic

Junmai Ginjo

Kuramitsu

Junmai Daiginjo

Koshihikari

Junmai Daiginjo

Koshihikari

Rice Lager

Koshi Tanrei 越淡麗

Koshi Tanrei is a Niigata sake rice that is ideal for making highly polished premium ginjo-shu. Sake brewed with it is often mildly fragrant with a light body and a soft, expansive texture. Tropical fruit and subtly ricey umami are also common notes.

The popularity of Koshi Tanrei within Niigata has grown steadily since it was registered in 2007. Over 1200 metric tons were produced in 2019– all in the prefecture. That ranked 10th in total Japanese shuzokotekimai production.

The origin of Koshi Tanrei resulted from a desire to make award-winning Daiginjo and Junmai Daiginjo with rice grown in Niigata. Gohyakumangoku has many great traits, but it doesn’t mill that well past 50%. Yamada Nishiki does, but has to be imported, as its tall height and late harvest don’t work so well in the cool prefecture. The two great sake rice varietals were crossed in 1989. It took 18 years of development to get to formal registration.

In the field, Koshi Tanrei is a high-yielder. This is despite being tall, top-heavy, and easily knocked over. It has large grains with a high degree of shinpaku. It polishes well to 40% or less– better even than Yamada Nishiki. It also steams well and is koji-friendly.

Popular Sake Brewed with Koshi Tanrei Rice

“Heaven and Earth”

Junmai Daiginjo

“Kagayaki”

Daiginjo Genshu

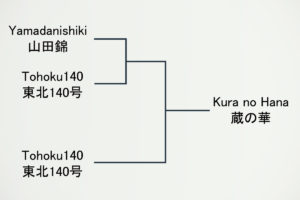

Kura no Hana 蔵の華

Kura no Hana is a Miyagi sake rice type that compares favorably to ubiquitous Miyama Nishiki. It tends to produce mellow sake that’s somewhat rich, medium-weight, and with a refreshing finish.

Kura no Hana was first cultivated in Miyagi in 1987. It’s a cross of Yamada Nishiki and Tohoku 140 (東北140号) with Tohoku 140. If you’re curious– Tohoku 140 is a cross of Chiyonishiki and Koganehikari– which includes Toyonishiki and Sasanishiki roots.

The actions that led to Kura no Hana’s creation were based on the desire for locally-adapted sake rice with character. One that would compete with Miyama Nishiki and Sasanishiki. And the results were successful, as Kura no Hana has a slightly larger grain size and weight per 1000 grains. It’s shorter, with improved lodging resistance. And last, but importantly: it yields much better. 2019 saw 917 metric tons produced– all of it in Miyagi-ken. That ranked 14th in total Japanese shuzokotekimai production.

Popular Sake Brewed with Kura no Hana Rice

Kura no Hana

Junmai Daiginjo

Kura no Hana

Junmai Daiginjo

Saka Nishiki 佐香錦

Sakanishiki is a Shimane sake rice with a lot of character. The sake it produces tends to be soft, with a deep flavor, and a crisp finish. Notes are variable ranging from umami to fruit depending upon milling and brewing style. Saka Nishiki is often used to make ginjo-shu.

Sakanishiki first came to be in 1985– the result of a Kairyo Hattanryo (改良八反流) and Kinmonnishiki (金紋錦) cross. The latter rice has Yamada Nishiki and Takane Nishiki as parents. Overall, that’s a pretty impressive lineage. But it took 19 years from inception to registration for Sakanishiki. It is primarily grown in the mountains and below 300 meters in elevation. Harvest is over a week after Gohyakumangoku– Shimane’s most popular sakamai. And Sakanishiki is somewhat intolerant of cold, meaning it can’t be planted too early.

This has kept the production volume low. 2019 saw 155 metric tons produced. That is up from only 68 in 2014.

Toji like Sakanishiki too for its moderately large grain size and ease of handling in the brewery. It mills well, meaning it doesn’t crack easily, and it’s also koji-friendly.

Popular Sake Brewed with Sakanishiki Rice

Sakanishiki

Junmai Ginjo Genshu

“Tsuwano Sakari”

Junmai Ginjo

Senbon Nishiki 千本錦

Senbon Nishiki is a premium sake rice from Hiroshima. It tends to make sake that is fragrant, with a rich flavor and a mildly bitter and fresh finish. It’s often used to brew ginjo-shu.

Yamada Nishiki and Nakate Shinsenbon are the parents used to cross Senbon Nishiki. It was first cultivated in 1990. The idea was to create a unique Hiroshima varietal that’s adapted to the climate and has excellent properties for making premium ginjo-shu. By 2002 Senbon Nishiki was registered, but its production volume hasn’t yet taken off. In 2019, 189 metric tons were produced in Hiroshima. However, an impressive 80% of that was graded Tokuto (Special Quality).

In the paddy, Senbon Nishiki delivers as a Yamada Nishiki alternative by being shorter and less prone to lodging. It also matures 8 days earlier on average in Hiroshima’s climate. In the brewery, Senbon Nishiki looks and behaves similarly to Yamada Nishiki for the most part– which is a very good thing. It has large grains– just over 26 grams per 1000 grains. Senbon polishes very well and it produces high-quality koji-mai to boot.

If a brewer in Hiroshima uses 100% Hiroshima-grown Senbon Nishiki, as well as complying with some quality assurance programs, it may be labeled as “Hiroshima Senbon Nishiki”.

Popular Sake Brewed with Senbon Nishiki Rice

Senbon Nishiki

Junmai Ginjo Hiyaoroshi

Aki-Agari

Junmai Yamahai

Senbon Nishiki

Junmai Daiginjo Genshu

Senbon Nishiki

Junmai Ginjo

Shinriki 神力

Shinriki is an heirloom sake rice strain that can make rich, savory, and herbal sake. It is very difficult to grow and its use had dried up for many decades. Even after its mini resurgence, it has not caught on strong. Production volumes have declined over the last 5 years from 86 metric tons produced in 2014– down to 40 tons in 2019.

Most of the Shinriki that is grown is of noteworthy quality. Kumamoto, Hyogo, and Fukui all produce the ancient grain. Miyake Honten (Sempuku) of Hiroshima also claims to be growing the grain starting from a handful of seeds they obtained.

Popular Sake Brewed with Shinriki Rice

“Sacred Power”

Junmai Ginjo

Shinriki 85

Junmai Kimoto Muroka Genshu

Yamadaho 山田穂

Yamadaho is the mother of Yamada Nishiki– the king of sake rice. It brings a lot of the great qualities of Yamada Nishiki, but because of its smaller grains, less shinpaku, and lower yields– it was almost entirely replaced. Yamadaho brews sake with a soft texture, depth, and a fresh finish.

The origin of Yamadaho is not clear, but it can be traced to at least 1877 when farmer Seisanburo Yamada (山田勢三郎) supposedly discovered the plant in his own field. Its large ears were noteworthy. He encouraged his neighbors to grow it as well, and it became well-known shipped under the name Yamadaho. There are two other stories linking the rice’s discovery to have occurred in Ise-shi, Mie as well as from Ibaraki-shi, Osaka.

Yamadaho is a very tall rice type– on average more than 10cm more than Yamada Nishiki. It’s much stronger though, and so has similar lodging resistance. Its sturdy stalks do make mowing post-harvest much more difficult and were another reason for its decline. It has smaller grains, with less shinpaku. It does absorb water well, with high digestibility, high amylose content, and very little protein. In 2019, 109 metric tons were produced– all within Hyogo prefecture.

The pure line selection Shin Yamadaho No. 1 (新山田穂1号) and No. 2 (新山田穂2号) were carried out in 1921 and 1922 respectively. The former is still grown today in Hyogo in modest quantities (15 metric tons, 2019).

Popular Sake Brewed with Yamadaho Rice

Yamadaho

Junmai Daiginjo

Yamadaho

Junmai Daiginjo

Yume no Kaori 夢の香り

Yume no Kaori is a popular shuzokotekimai from Fukushima prefecture. It tends to produce soft, medium-body sake. It’s often paired with aromatic and fruity Fukushima yeast to make ginjo-shu. This sake rice came from the desire for a local strain that’s adapted to the cooler climates of the prefecture while providing a superior alternative to Gohyakumangoku.

And in that regard, Yume no Kaori has been a success. Its grains are equally as large as Gohyakumangoku, with high rates of shinpaku, and slightly improved brewing quality. Yume no Kaori is fairly cold-resistant and is not felled easily by wind. Still, it is not commonly grown in cooler, flat northern Fukushima and Iwaki City (いわき市), as well as on higher altitude paddies.

Yume no Kaori was first cultivated in 1991 in Fukushima– a cross of Hattan Nishiki No.1 (八反錦1号) and Dewasansan (出羽燦々). That’s an impressive pedigree. By the year 2000, Yume no Kaori was recommended for Fukushima sake brewers. Production has been steadily on the rise. In 2019 961 metric tons were harvested– 13th in Japanese sake rice production. That’s more than double 2014’s volume.

Popular Sake Brewed with Yume no Kaori Rice

Yume no Kaori

Tokubetsu Junmai

Yume no Kaori

Junmai Daiginjo

“Karahashi”

Junmai Ginjo

Yume no Kaori

Junmai Ginjo

Sources and Acknowledgments

This page relied heavily on data from official Japanese government and agricultural research organization sources. Additionally, studying sake with the Sake School of America (SSI) and its resources have taught me a lot about sake rice, as well as sake and shochu overall. Lastly, the educator and sake legend John Gauntner, through his books and website (Sake World), has also been a great aid in advancing my sake knowledge.

National Agriculture and Food Research Organization: NARO

Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries: MAFF

Follow the Japanese Bar on Social Media

Connect with our latest posts, the newest Japanese beverage info, and get exclusive promotional offers. Level-up your sake IQ!

Brad,

Hello from Tahoma Fuji. This is a fantastic review of sake rice. Thank you for putting the time into this resource. Very well done.

On a personal note, I hope you have been well. I miss chatting with you and hope to run into each other in the future.

Hi Andy!

I’m glad you like my rice pages. And it’s nice to hear from you. I hope we can get together soon and enjoy some Tahoma Fuji.

Brad

This is by far the best information about rice suitable for brewing sake.

Well done!

Keep up the good work

Burkhard / Germany

Thank you very much! It was a fun project. I will be adding more info soon including other sake rice types.