Do you like sake but have a hard time knowing what to buy? There is no faster way to change this than by learning the types of sake.

In this article, we’ll teach you the basics so you can start choosing sake with confidence. You can also improve your next dining experience with our service and pairing tips.

We’ll start with the fundamentals: sake grades. After that, we’ll move on to the additional brewing choices (styles) that can be applied on top of the sake grades.

Sake Type 101: What is a Sake Grade?

To understand the different types of sake, it helps to know some basic facts.

Rice Milling

Rice is used to make sake, as you probably already know. And it’s typically polished to remove some of the outside (hull, bran) layers. These outer layers also house a lot of protein, which isn’t usually desirable in sake brewing.

What brewer’s really want to use is the starchy core of the rice grain. The more they mill their rice, the lighter and smoother their sake will become.

Want to learn more about sake rice? Check out our Sake Rice Guide. We cover the 36 most important sakamai in detail.

Pure Rice vs Added Alcohol Sake

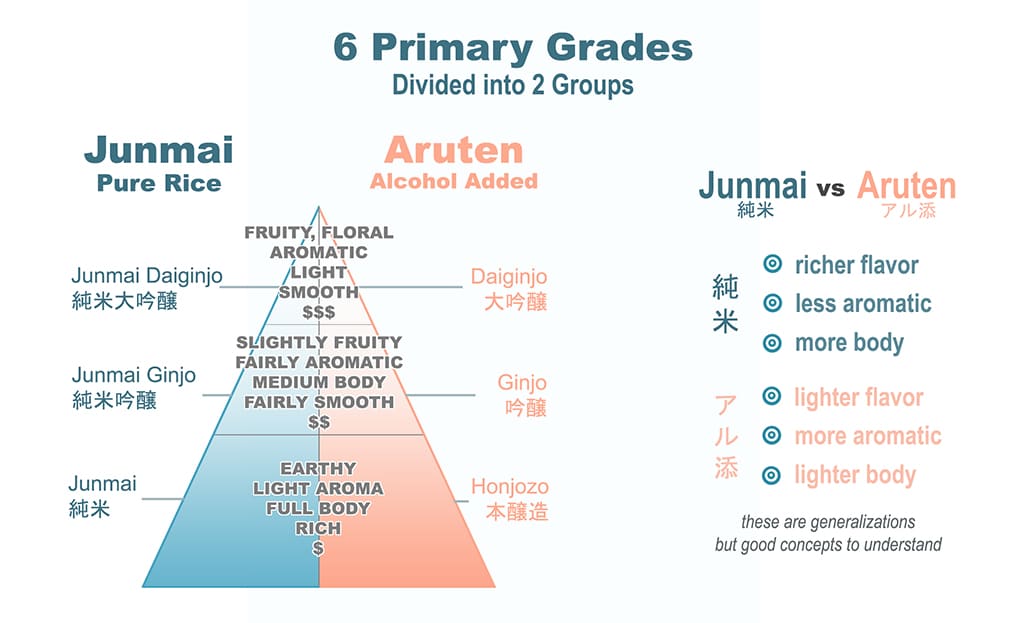

There are two broad types of sake: junmai and aruten.

Junmai means “pure rice”. These sakes are made with just rice, rice koji, water, and yeast.

Aruten is the other main category. These types of sake allow the addition of a small amount of neutral spirit (similar to vodka). This tends to make the sake more aromatic. Later, water is added to the sake to reduce the alcohol strength. By diluting the sake, it makes the flavor lighter. Aruten sake often features a mild burn on the finish.

Broadly speaking, junmai sake types will be more robust and less fragrant, whereas aruten types are more aromatic and lighter in body.

The Official Sake Grades

Below are the quality sake designations. Any sake that qualifies will list one of these grades on the bottle. Most of the sake exported from Japan will be one of these grades.

Once you’re familiar with these, picking sake that you like will be a lot easier.

Please keep in mind: the flavor profiles of the sake grades below are generalizations. With most things in the sake world, there are sometimes exceptions.

Futsu-shu 普通酒

(fuut suu shuu)

Futsu-shu is a broad category of sake. It has fewer quality regulations than the premium grades listed below and can be considered “table sake.”

Futsu-shu permits more added alcohol than premium types of sake. It also has no minimum milling requirements and allows the addition of sugar and other additives.

The term futsu-shu (普通酒) rarely appears on labels. However, if a sake qualifies as a premium grade like junmai or ginjo, it will say so. Therefore, futsu-shu can often be identified by its lack of a premium grade on the label.

Junmai 純米

(juun my)

Junmai is the earthiest, heaviest, most bitter, acidic, and least aromatic of the premium sake grades. Savory umami and mineral notes dominate with fruitiness subdued. Junmai sake is usually flexible in serving temperature. It also pairs with a wide variety of cuisine.

Junmai is typically milled to a minimum of 70% remaining but has no legal milling standard. No neutral spirit is allowed.

Honjozo 本醸造

(hawn joh zoh)

Honjozo is another savory and robust sake but is often lighter and more aromatic than Junmai. Mineral and grainy notes are common. Fruitiness is restrained, and many are slightly sweet.

Warm honjozo is usually pretty tasty.

Rice must be polished to a minimum of 70% (remaining) to qualify. The addition of jozo alcohol (neutral spirit) and water increases the yield and affordability.

Tokubetsu 特別

(toh koo bet soo)

Both tokubetsu junmai and tokubetsu honjozo are made. They have a well-balanced profile. There is usually some aromatic, fruity, and light character, with the savory, solid core of junmai or honjozo. These are medium to full-bodied sake.

Tokubetsu pairs well with a variety of dishes.

Tokubetsu means “special”. What is special isn’t always clearly defined, however. Often the rice is polished ≥ 60% with hands-on brewing methods used. Sometimes a local or premium rice strain or yeast is used.

Interested in learning about sake yeast? Take a look at our Sake Yeast Guide. We cover over 25 types and their flavor profiles.

Junmai Ginjo 純米吟醸

(juun my geen joh)

Junmai ginjo sake is typically aromatic with fruity and floral notes dominant. They’re also usually medium-bodied and smooth. A mild savory character may be present.

Like any sake, junmai ginjo can range from sweet to dry but is often drier.

Junmai ginjo pairs well with a wide variety of food— but it’s best to avoid heavy flavors. Usually best served from chilled to room temperature.

Rice must be polished to a minimum of 60% (remaining) to qualify. No neutral spirit is allowed.

Ginjo 吟醸

(geen joh)

Ginjo sake is similar to junmai ginjo, but is even lighter and more fragrant. Acidity is typically lower as well, which can lead to a softer texture. Ginjo often finishes with a faint burn.

Ginjo is a great choice for sushi and lighter dishes. It typically shows best chilled. Small cups (o-choko) will make the sake seem lighter. Stemware is a great alternative for highlighting aromatics and structure.

Rice must be polished to a minimum of 60% (remaining) to qualify. Ginjo has a small amount of neutral spirit added.

Junmai Daiginjo 純米大吟醸

(juun my die geen joh)

Junmai daiginjo is a light, fruity, floral, and fragrant type of junmai sake. Quite clean and typically free of bitterness. Umami may be present in the background. Junmai daiginjo requires rice milled to at least 50%. Brewing is also hands-on. This increases cost.

Heating can reduce aromatic intensity and subtlety— so junmai daiginjo is usually best served chilled.

Rice must be polished to a minimum of 50% (remaining) to qualify. No neutral spirit is allowed.

Daiginjo 大吟醸

(die geen joh)

Daiginjo sake is even lighter, more aromatic, and cleaner than junmai daiginjo. Fruity, floral, soft, and smooth—daiginjo is pretty. May still finish with a touch of heat.

Daiginjo is a classic pairing with sushi. It’s also best chilled. This sake shows well in stemware and can almost disappear in smaller o-choko.

Daiginjo must be milled to a minimum of 50% and is made with the addition of a small amount of neutral spirit.

Mashing: Shubo 酒母 / Moto 酛

The fermentation (mash) starter for sake is called shubo or moto. It consists of koji rice, steamed rice, water, and yeast. Lactic acid is also an important component for spoilage prevention.

The shubo method used has a big effect on a sake’s flavor profile. Below we list them from the oldest method to the newest.

Bodaimoto 菩提酛 or 菩提もと

(boh die moh toh)

Bodaimoto, or mizumoto (水酛), is an old-school shubo method of Buddhist origin. It’s considered the first modern sake starter. Once the kimoto (listed below) method was adopted, bodai moto fell out of favor. It’s made a quiet comeback in the last couple of decades, however.

Sake made with the bodaimoto tends to have a strong lactic character. Some examples can be quite funky, as well. Elevated acidity is another common characteristic.

Kimoto 生酛

(kii moh toh)

Kimoto was developed after bodaimoto and is considered a traditional shubo method. The laborious yamaoroshi (山卸し) method is used, with heavy mixing of the mash using oar-like paddles. This produces the lactic acid needed to protect against spoilage.

Kimoto sake is often funky, earthy, and acidic. They’re also often good served from chilled to hot.

Learn more about kimoto sake here.

Yamahai 山廃

(yah mah high)

The yamahai moto method is much newer than bodaimoto or kimoto. A warmer mash temperature replaces the hard work of the yamaoroshi process, but the resulting sake is similar in flavor. For these reasons, yamahai largely replaced the kimoto method.

Dive deeper into yamahai sake here.

Sokujo Moto 速醸酛

(soh kuu joh moh toh)

The sokujo-moto method came about around the same time as Yamahai. Commercial lactic acid is added to the mash inhibiting unwanted bacteria. It’s an easy method and much faster than the previous shubo styles. This has made it the default style of sake mash production.

Sake made with the sokujo-moto method tends to be clean, elegant, and modern. Unlike the moto methods above, sokujo-moto almost never appears on the label.

Learn more about sokujo-moto here.

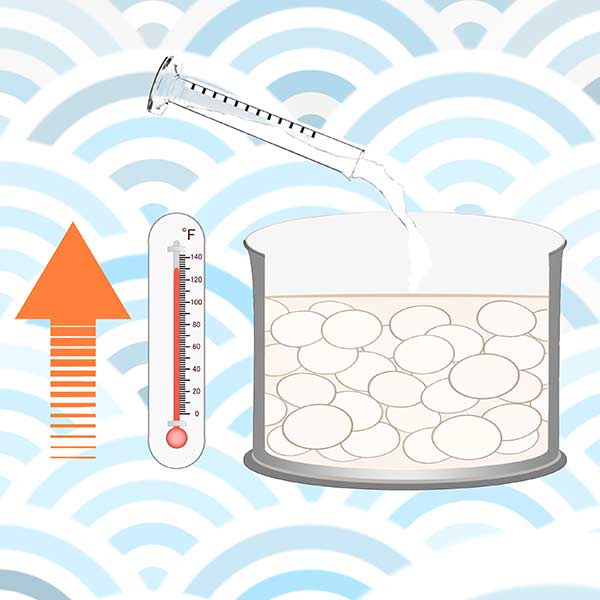

The koontoka (高温糖化) sub-style ferments even faster and warmer than sokujo-moto. Temperatures above 120 F are needed. koontoka produces fruity and fresh sake.

Click here to learn more about koontoka sake.

Pressing – Jozo 上槽

To make sake, the fermented mash must be pressed. This separates the solids (lees) from the liquid. Brewers typically use either a modern automatic press or the more traditional fune.

Shizuku 雫酒

(shee zuu kuu)

Shizuku means “sake droplets,”, because the mash is suspended in bags, and only what drips freely is collected. This is a difficult and inefficient older method.

Shizuku is rare and often expensive. The quality of shizuku sake is high, however. It tends to produce extremely elegant sake.

Alternative names for shizuku include fukurozuri (袋吊り), tobinkakoi (斗瓶囲い).

Learn more about shizuku sake here.

Arabashiri あらばしり

(ah rah bah shee ree)

Arabashiri is the sake that pours freely without pressure inside a fune. Meaning “rough run,” arabashiri has a more astringent character than the sake that results from the subsequent second pressing (nakadori 中取り).

Arabashiri sake is usually vibrant and brash in taste.

Shiboritate しぼりたて

(shee boh ree tah teh)

Shiboritate is a type of sake that’s bottled shortly after pressing, usually unpasteurized. It is released early in the brewing season, becoming available in late fall or winter.

This “fresh-pressed” sake is zippy and youthful in flavor.

Pasteurization – Hi-ire 火入れ

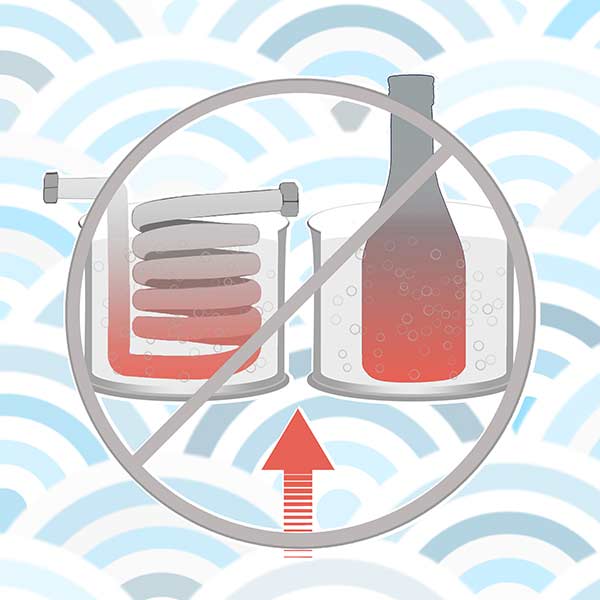

Sake spoils easily, so it’s typically pasteurized after pressing and again at bottling. Heating ceases microbial activity, adding to the sake’s shelf-life and stability, but it also mellows flavor and intensity.

Namazake 生酒

(nah mah zah keh)

Namazake is unpasteurized sake. It’s sometimes called nama-nama, draft sake, or just nama. Most breweries release a nama each spring as one of their first releases of the season. Namazake is easily spoiled and must remain cold until it’s served.

Namazake is a type of sake that’s usually bold and acidic. Bitterness on the finish is also common.

Learn more about unpasteurized sake here.

Namazume 生詰め

(nah mah zuu meh)

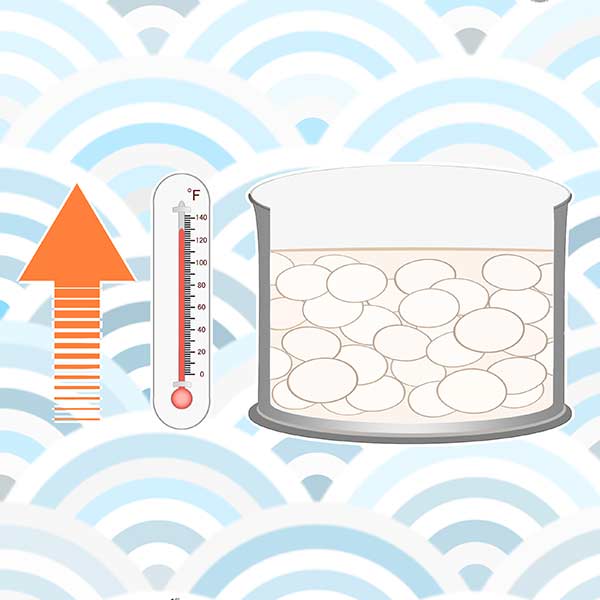

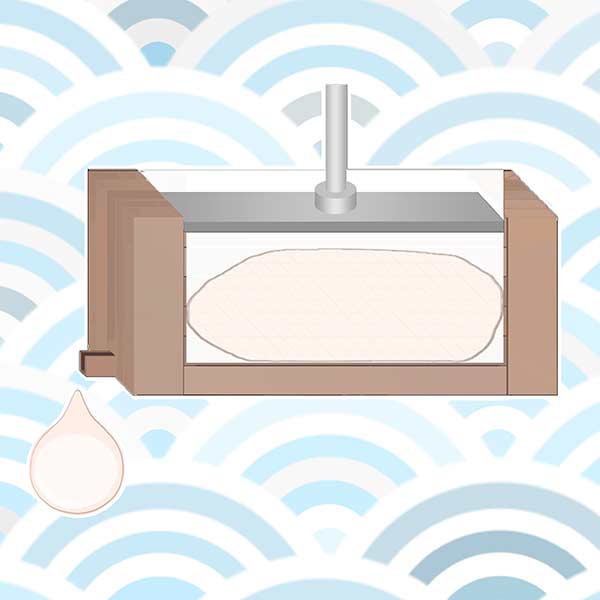

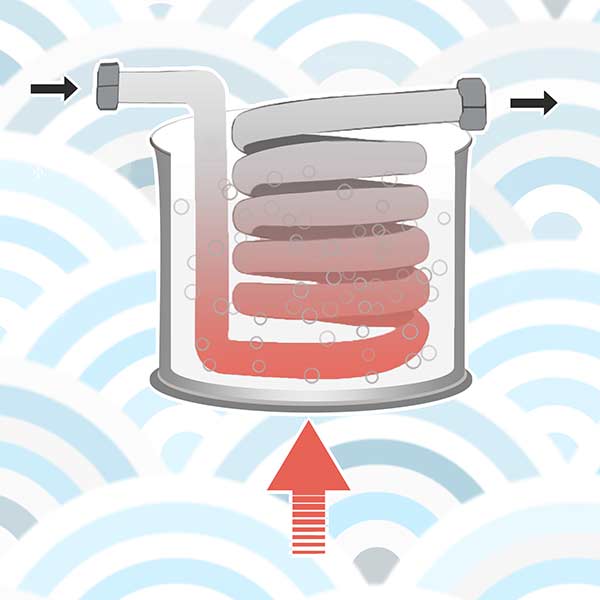

Namazume is pasteurized once, after pressing. This is often done by passing sake through an immersion coil inside a hot water bath.

Namazume sake retains a little extra freshness and vibrancy in taste. It’s not as bold as namazake, but it is much more stable.

Namachozo 生貯藏

(nah mah choh zoh)

Sake that is pasteurized only once during or after bottling is called namachozo.

It has some of the zip and vibrance of namazake with more resistance to spoilage. Namazume and namachozo have similar flavor profiles.

Hiyaoroshi 冷や下ろし, ひやおろし

(hee yah oh roh shee)

Hiyaoroshi is a fall-release sake that’s brewed in spring and usually pasteurized once (namazume). It’s then cold-stored over the summer, becoming available in the fall.

This seasonal sake is a little more vibrant than standard (twice-pasteurized) sake. It also often slightly savory.

Other Sake Types

Below are a mix of common brewing choices and rarer specialty types of sake.

Muroka 無濾過

(muu roh kah)

Muroka is a type of sake that’s “unfiltered” by charcoal. Most sake is filtered for stability and to refine the flavor.

Muroka sake has a full body and flavor with more color. It’s often paired with nama and genshu (see below) brewing techniques.

Learn more about muroka sake here.

Genshu 原酒

(gen shuu)

Genshu sake is undiluted with water. This means it’s typically strong and full-bodied. There are exceptions, of course.

Genshu also tends to have some sweetness. The alcohol content can range from 16%-22%, and averages 18%-20%.

Learn more about genshu sake here.

Nigori にごり

Nigori means “cloudy”, since some of the sake lees (kasu) are bottled with the sake. This type of sake is often erroneously called unfiltered sake. This isn’t true because nigori is either coarse-filtered, or it is completely filtered with some amount of lees being placed back into the clear sake. Usu (uu suu) nigori (うすにごり) is a thinner, less cloudy variation.

Nigori is often sweeter, thicker, and grainer than clear sake. The more clouds (lees), the more pronounced these traits can be. Serve from cold to room temperature.

Sparkling スパークリング or Happo-seishu 発泡清酒

(hahp poh say shuu)

Sparkling sake is a variable, newer sake type. Forced carbonation, secondary fermentation in bottle or tank, and even traditional-method wine techniques are all used to create CO2.

Most sparkling sakes are light, low alcohol, and sweet. Some are cloudy. Dry sparkling sake is higher in alcohol and aims to compete with sparkling wine.

Tanrei 淡麗

(tahn ray)

Tanrei is a term for a light and elegant flavored sake. It’s often brewed to be dry tasting (see karakuchi below), as well.

Sashimi is a delicious match with this mild-flavored sake style.

Karakuchi 辛口

(kah rah kuu chee)

Karakuchi is dry sake type. If the term (or o-karakuchi 大辛口) appears on the label, the sake will likely be exceptionally dry.

Taru Sake 樽酒

(tah ruu sah keh)

Taru sake has been aged for a period of time in cedar barrels. Between one and four weeks is common. All sake was brewed and stored in cedar before steel became available. Today, taruzake is much less common.

This type of sake does have a noticeable flavor of spicy, herbal cedar. It can be very good warm, especially when not overly dry in taste.

Koshu 古酒

(koh shuu)

Koshu is “old sake” that has been intentionally aged, usually for three or more years. It develops a nuttier, oxidized, and increasingly savory profile with time. Color also will darken with time.

Most sake is best consumed fresh, and koshu is therefore an uncommon sake type.

Kijoshu 貴醸酒

(kee joh shuu)

Kijoshu is a type of sake made by replacing some of the water used for brewing with finished sake. The alcohol in the sake stops the yeast from creating more alcohol. The added sake does not stop the koji from making more glucose (sugar) from the rice, however.

Kijoshu is usually sweet and unctuous. With age, this style can develop umami, color, and Sherry-like qualities. Kijoshu is excellent with ice cream or strong cheese.