The production process of whisky is unique to the spirits world. The combined requirements of a starchy cereal grain mash AND oak aging make it so.

If you’re wondering how whisky is made: this step-by-step guide is for you. Below we’ll break down the handful of steps that produce this wonderful spirit. Additionally, the primary whisky still types are detailed.

This is part two of three articles covering the basics of whisky. Part one answers the fundamental question: What is Whisky?

Malting, Milling, and Mashing

Whisky production begins with its ingredients. The mash bill (aka grain bill, grain recipe) is the composition of grains used to make the whisky. As mentioned previously: barley, corn, rye, and wheat are the most common grains used. Oats, rice, and other grains are also used in regions where they’re grown.

All of these cereal grains share a relatively starchy composition that doesn’t ferment easily on its own.

Of all the grains used to make whisky, barley is arguably the most valuable.

Malting and Saccharification

So what makes barley so prominent in whisky production? The primary reason is that it contains a high level of enzymes (diastase and alpha-amylase) that, after sprouting and heating (malting), can easily convert starch into fermentable glucose. The conversion process is called saccharification.

This reaction is strong enough that even a small amount of this malted barley in the grain bill can convert the whole batch to fermentable sugar. Other grains are malted in this way in place of barley– they’re just not as enzymatically active.

This process of malting begins by germinating the barley in water. The sprouting of the grains forms the enzymes. This sprouted grain at this point is called green malt. The green malt is then heated in a kiln which stops germination.

The amount of heat applied and the time spent roasting will have a big impact on the final whisky. The use of peat to heat and smoke the malt is an option that can also have a big impact.

The Whisky Mash

After this modification process, the barley is simply called malt or malted barley. The malt will be milled down into grist, along with any other grains in the mash bill.

The ground-up grains will be placed into a mash tun or mash cooker where hot water is added. This cooks the grains, liquefies the remaining starch, and activates the enzymes which begin to convert the rest of the grains into fermentable sugars. Once this step is complete the liquid is ready for fermentation and is either separated from the solids or kept together (US whiskey). This sugary liquid is called the mash or wort.

It’s worth noting that the water used for malting and mashing will have a big impact on the flavor and texture of the resulting whisky.

Recommended Whisky Products

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Fermentation: Beer Before Whisky

At this stage in the whisky-making process, there is still no alcohol. For that, yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) will be needed. The sweet wort will be placed into a washback or an open fermenter and already contains some ambient yeast.

The distiller will typically add either commercially available distiller’s yeast (DADY), their own proprietary yeast, or even ambient yeast. The yeast used for distillation can usually handle a higher alcohol content than the yeast used for brewing beer.

The final fermented beer, or wash, will usually be between 8% and 14% abv. Beer is an appropriate term, because at this point: the fermented brew is literally beer without hops. It’s pretty cool that whisky production begins with the process of brewing beer!

How Whisky is Made: Distillation

If whisky is made from beer: what’s the difference?

The answer is distillation, which is a process of concentrating alcohol (ethyl alcohol or ethanol) to the desired strength by separating it from water and some of its other dissolved components.

This will be done in a closed still and relies on the difference in boiling points between water (212° F) and ethanol (173° F) to capture the concentrated alcoholic vapor.

Because of its lower boiling point: ethanol will vaporize faster than water. Some of the vapor will fall back into the still as reflux, while some of the vapor is collected and cooled back into liquid form for further processing.

The Cut Points and Quality

This alcoholic gas is not uniform and the quality of the final spirit will be majorly impacted by what parts make it into the final product and which don’t make the cut.

The first gasses to arise upon heating of the wort are called low boilers, heads, or the foreshot. These more volatile components are not considered potable and will typically be redistilled.

The middle part of the distillation run contains the best stuff and is usually called the heart. The heart contains fewer undesirable congeners that adversely affect the flavor (or will make you go blind).

Once much of the wort has been boiled off, the vapor again begins to feature more nasty congeners, this time called high boilers, the tail, or feints. Again: you don’t want this stuff in your whisky. It will also often be redistilled later.

The points separating the head, heart, and tail are called the cut points. A skilled distiller will leave out the bad stuff while retaining as many desired congeners as possible. Cutting out the heads and tails aggressively will lead to fewer congeners and a smoother spirit but also one that is more neutral in aroma and flavor. A distiller is able to determine the cuts by sampling and analyzing the colorless new make spirit in a spirit safe connected to the still.

At this stage in the process, water is often added to the new make to adjust the alcohol content down to around 62%.

Maturation: Oak Barrel Aging

The final major step in how whisky is made is barrel aging. All whisky requires it to some extent. Without oak aging, the final product is really just moonshine or strong-flavored vodka. Sometimes this clear spirit will be bottled and labeled (erroneously) white whiskey or white dog. Without oak contact and time, this stuff doesn’t resemble whisky.

The processes involved in barrel aging are complex and deserve their own post. Check out part three of this whisky basics series: Oak Casks and Aging Whisky.

Post-Maturation: The Final Adjustments

Most of the work is done at this point of the whisky-making process. The final steps often include blending similar-flavored whiskies into a final product suitable for bottling.

Purified water will typically be added, carefully, to adjust to bottling strength. The optional final steps include filtration, as well as the addition of caramel coloring for consistency.

Types of Whisky Stills

Now that we’ve covered the steps involved in whisky production, let’s dive a little deeper into stills. The distillation of whisky, and other spirits, happens in a still.

There are a few main types of stills in use today. The type used and its specific characteristics will go a long way in determining the overall character of the resulting whisky.

Regardless of the type of still, copper will typically be used wherever alcoholic vapor or liquid might come into contact with the still. Copper does an amazing job of stripping much of the worst congeners from the resulting spirit.

The more time water/alcohol vapor comes into contact with copper, the lighter and smoother it will become.

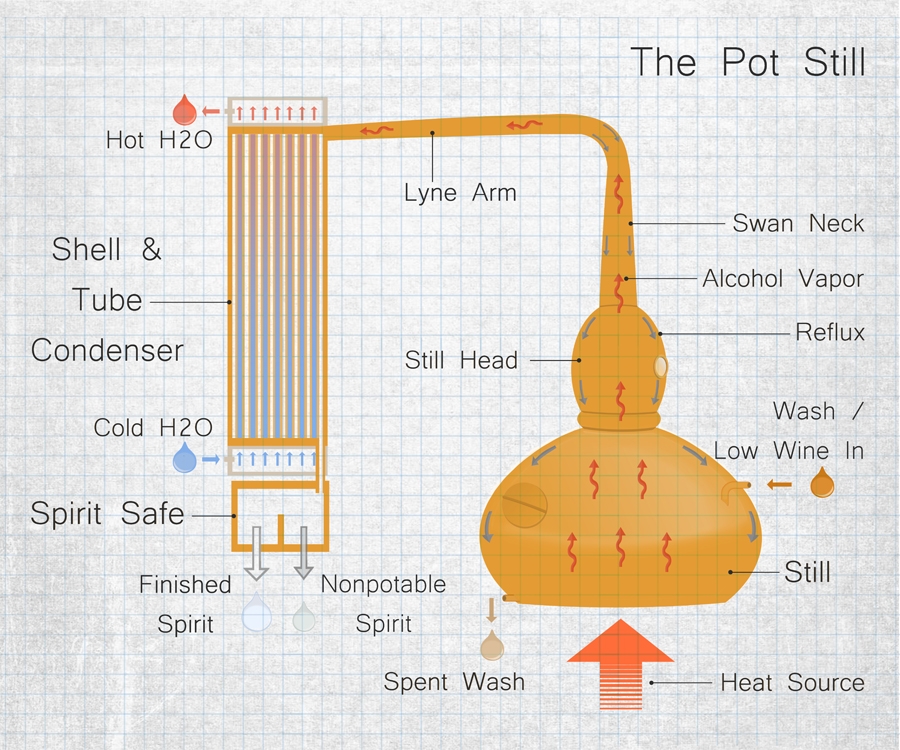

The Pot Still

When one thinks of making whisky, the pot still often comes to mind. This old design consists of two major components: the still itself where distillation happens, and a condenser where the alcoholic vapor is cooled back into liquid form. The bulbous pot still has a wide base and a long, tapered top called a swan’s neck which leads to the condenser.

ll is a batch process. Typically, the wort is first distilled in a wash still. The resulting spirit, called low wines, is about 25% abv. It’s then placed into a second still called a spirit still. Inside the heated low wines are further distilled and usually come off the still between 55% and 70% abv. Sometimes three or more distillations happen in a pot still but two is the most common.

Learn more about pot stills here.

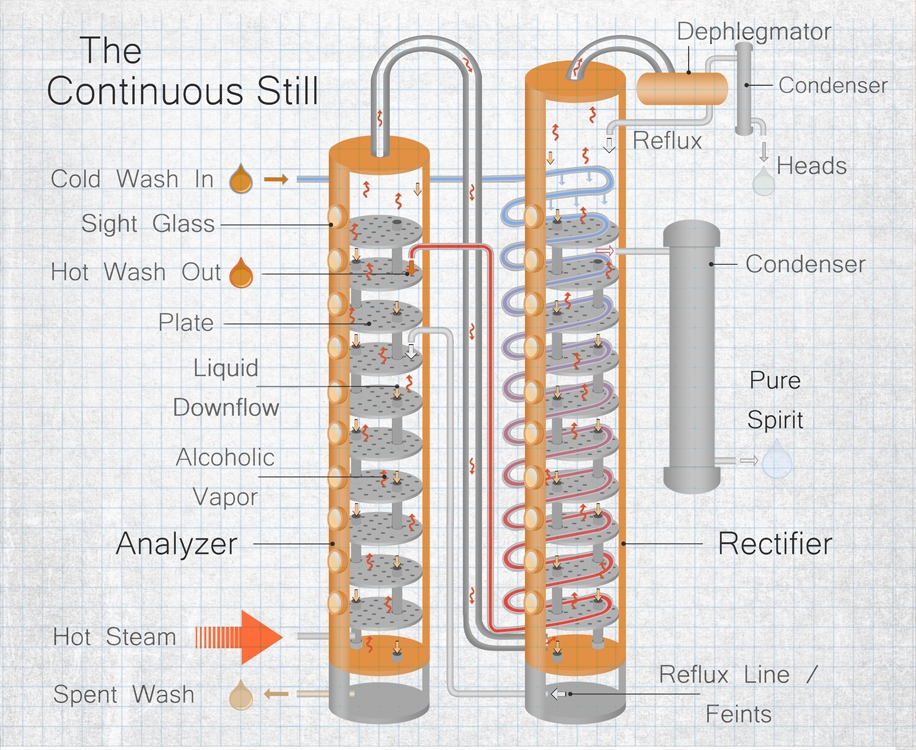

The More Efficient Continuous Column Still

The column still is an industrial design that makes a higher-proof spirit. It’s the still of choice for grain whisky, as well as vodka and many industrial rums.

Learn more about column stills here.

The Hybrid Still

A hybrid still is a combination of a pot and a single column still. The results are more akin to the latter than the former. Its design consists of a pot still base where the wash is heated with a single rectifying column on top of that.

Again, a condenser sits atop the rectifier.

A hybrid still is fairly simple and more efficient than a pot still. This has made it a popular choice amongst smaller distillers.

Related Whisky Posts

- The Japanese Whisky Guide: Understand the Market, History, Popular Brands, and the Brands to Avoid

- The Top 13 Japanese Whiskies Under $100: No Fakes